By Donovan Martin Sr, Editor in Chief

Political ideology is one of the most powerful forces shaping our lives, yet most of us rarely pause to examine how deeply it governs the way we think, feel, and act. From an early age, we are immersed in the political leanings of our parents, grandparents, and communities. Whether it is Republican or Democrat, Liberal or Conservative, Likud or Labor, each generation inherits a script of beliefs, values, and fears that become almost second nature. By the time we reach adulthood, these scripts are so ingrained that they feel less like choices and more like immutable truths.

Intelligence agencies such as the CIA have long noted that after age twenty-five, the likelihood of changing one’s political ideology drops dramatically—down to less than five percent. The implication is sobering: no matter how much new evidence, no matter how catastrophic the failures of a chosen ideology, the vast majority of us will not abandon it. Politicians know this. Corporations know this. Institutions know this. They build entire strategies around the assumption that loyalty is fixed and that all they must do is hold their base, occasionally converting a few independents, while demonizing the opposition to keep everyone else in line.

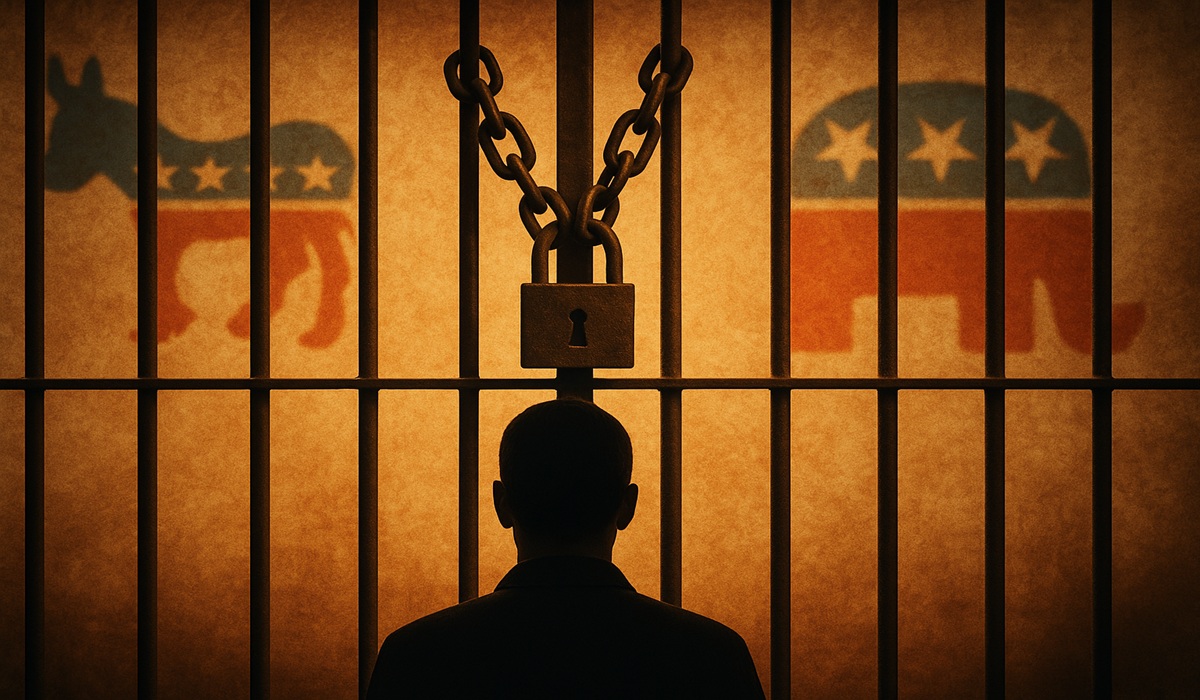

But if this is true—if political ideology is effectively a lifelong prison—then what does this say about democracy itself? Are we truly choosing our leaders, or are we simply reenacting our conditioning, reaffirming our family’s biases, and allowing our society’s divisions to calcify beyond repair?

Our earliest political education happens without us realizing it. Children absorb the quiet sighs of disapproval when a certain politician’s face appears on the television. They listen to conversations at the dinner table about taxes, social programs, war, and morality. Even before they can vote, they know which party is “ours” and which party is “the enemy.” Later, when they come of age, their first ballot is less a personal decision than a confirmation of loyalty.

This pattern repeats across nations. In the United States, the “red” states cling fiercely to Republican ideals, even when Republican trade wars devastate the very industries that sustain them. Farmers whose livelihoods collapse under tariffs still cast ballots for the same leaders who engineered their downfall, because switching allegiance would feel like betraying family, heritage, and identity. In Canada, Liberal policies that overreach and strain the economy are tolerated by their base, who see the alternative—Conservatives—as a betrayal of progress. In Israel, the far-right dominance of Netanyahu’s Likud party has entrenched a vision of society so deeply that the possibility of moderation feels almost unthinkable.

Across the globe, ideology operates less like a marketplace of ideas and more like a hereditary monarchy, passed down through generations. The illusion of freedom exists, but the hand guiding our choices was placed upon us long ago.

Politicians understand the permanence of ideological indoctrination. Once elected, they govern not with the fear of losing their base, but with the confidence that their base cannot leave. Their greatest challenge is not to persuade, but to maintain the loyalty of the faithful while converting just enough swing voters to hold power.

This dynamic explains why leaders can inflict massive harm on their constituents without fear of mass desertion. President Trump’s trade wars decimated the farming, auto, and chip sectors, yet his support remained unwavering in many red states. The very people who bore the brunt of his policies continued to defend him, not because they were blind to their suffering, but because they were trapped in the prison of ideological loyalty. Likewise, left-leaning governments across the world can impose crippling taxes, overextend welfare programs, or mishandle crises, yet remain buoyed by their base because the alternative feels existentially worse.

This stranglehold is amplified by media ecosystems that cater to ideological bubbles. Conservative voters consume conservative news; liberal voters consume liberal news. Each outlet reinforces the worldview of its audience, shielding them from contradictory information. Politicians and their media allies manufacture propaganda, spin narratives, and amplify outrage, not to change minds but to harden them further. The result is a populace convinced of its righteousness, immune to persuasion, and willing to endure immense suffering so long as the enemy does not win.

Democracy is built on the premise that citizens act in pursuit of the greater good. But what if the “greater good” does not exist—at least not as a universal value? What if every political ideology simply redefines the greater good as “what benefits us and our people”?

Consider healthcare. For conservatives, reducing government involvement is the greater good, even if it means millions remain uninsured. For progressives, universal healthcare is the greater good, even if it requires higher taxes and slower economic growth. Each side frames its position as serving society, but beneath the rhetoric lies a narrower truth: each side is fighting for what benefits their people, their donors, their corporations, their families.

This is not limited to democracies. In authoritarian systems, leaders define the greater good as the perpetuation of the state or the survival of the ruling class. In conflict zones like Israel and Palestine, the greater good is equated with the survival of one’s nation, one’s faith, one’s people—at the expense of the other. To speak of a universal greater good in such contexts is almost laughable.

So perhaps the haunting question is not whether our leaders are serving the greater good, but whether the greater good is even possible. Are we, as societies, capable of transcending our narrow interests and truly imagining a good that includes those we despise, fear, or exploit?

If ideological indoctrination is so strong, if our minds harden by twenty-five and remain fixed for life, then what hope is there for transformation? Can society evolve if its citizens cannot change?

Some argue that the hope lies in the youth. Each new generation, unburdened by the scars of the past, may carve out a new political direction. Yet even this optimism feels fragile. Youth are still born into households where ideology is inherited. They still attend schools where certain narratives dominate. They still scroll through feeds where algorithms amplify outrage and mimicry. By the time they come of age, many are already ensnared.

Occasionally, crises crack the walls of indoctrination. A war that exposes the futility of nationalism, an economic collapse that shatters faith in markets, a pandemic that proves the necessity of collective action—such events can force people to reconsider their ideology. Yet even then, the effect is uneven. Some emerge transformed, others only double down.

The reality is bleak: systemic change rarely comes from within the system of voters. It comes from upheaval—mass protest, revolution, collapse, or generational turnover. Until then, the cycle repeats: loyalty, betrayal, suffering, loyalty again.

If ideology is a prison, then how do we escape? Perhaps the answer is that we cannot. At least, not fully. But we can begin by acknowledging the prison itself. To admit that our beliefs are not divine truths but conditioned reflexes is the first step toward humility.

Education could play a role, but not the kind that simply teaches facts. Rather, an education that fosters critical thinking, exposes students to multiple perspectives, and teaches them to question not only their opponents but themselves. Media literacy could help dismantle propaganda’s grip, though it requires a willingness to engage beyond the echo chamber.

Yet even here, the solution feels limited. If only five percent of adults will change their ideology after twenty-five, then what we are really doing is planting seeds in the young and hoping they grow differently. The older generations remain largely fixed. The political system continues as is.

And perhaps the most unsettling question of all: if people were freed from ideology, what would guide them? Is human society even capable of organizing without belief systems that divide us into tribes? Would freedom from ideology create chaos rather than unity?

Political ideology indoctrination is not just a quirk of human psychology—it is the foundation of our political systems. It sustains leaders in power even as they destroy the very people who elect them. It turns the concept of democracy into a ritual of loyalty rather than an exercise of reason. It redefines the greater good into smaller, narrower goods that serve only factions.

We like to think we are rational beings making free choices, but the truth is far harsher: most of us are simply echoing the voices of our parents, our communities, our media. We are captives in the prison of ideology, and the wardens—politicians, corporations, institutions—know that we cannot leave.

The question that remains is whether we can ever look into the mirror and see the prison for what it is. And if we do, will we have the courage to walk out of it—or will we retreat back into the safety of our chains, waiting for the next election, the next promise, the next betrayal, while society marches on unchanged?