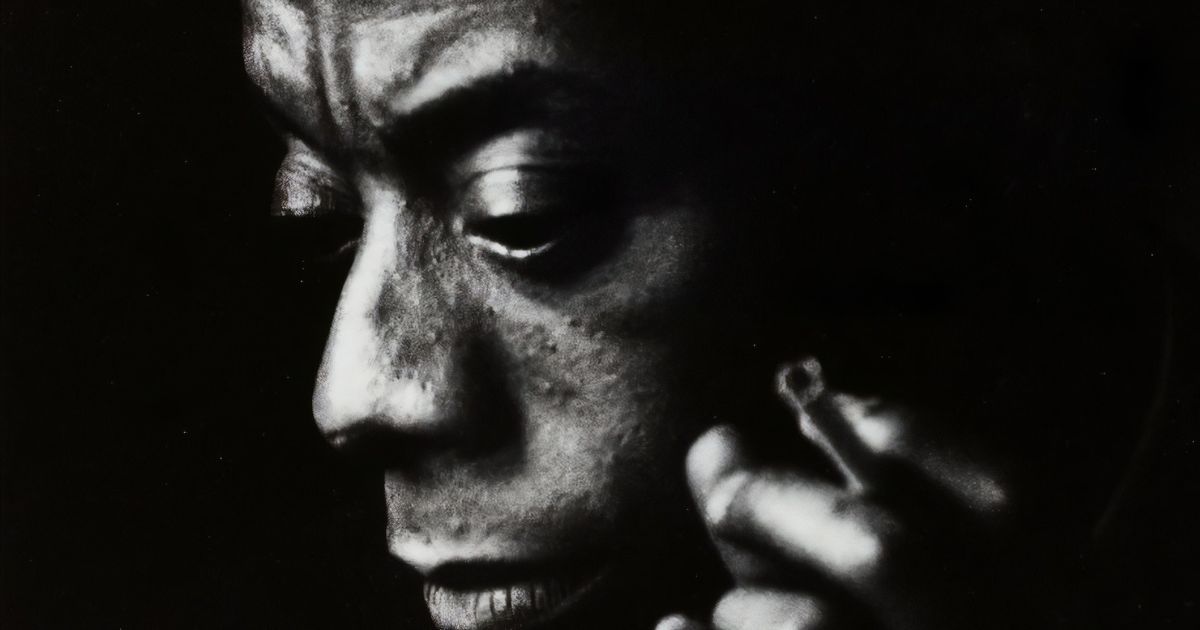

“There was not, no matter where one turned, any acceptable image of oneself, no proof of one’s existence.”

It’s never too late in the day to open fresh artistic discussions about James Arthur Baldwin, one of the gigantic figures in American and world letters. Very few sustained dialogues about the renowned author would take place without meandering towards the site of sexuality and identities in his popular books and essays. But racial tensions between blacks and whites, poverty, suicide, national and international politics, religious issues, the sins of slavery, and the dominance of the rich over the poor, are some of the thematic elements encountered in the many stirring essays and public debates of James Baldwin, the late Black-American novelist, playwright, and essayist, who was born on August 2, 1924 and died on December 1, 1987. James Baldwin lived influential parts in most of the experiences and tensions he wrote about. The most affective parts of his writing world were clear and haunting reflections of his dark, closeted spaces. But something else also haunted James Baldwin all his life, what the author robustly framed as “the stigma and danger of being a Negro.”

A Difficult Identity

James Baldwin was intensely infuriated by the popular perception of his racial beauty and sexual identity. He was haunted from unexpected and familiar corners. Indeed, his sexuality was a burden hunched on his back by the world everywhere he went. In many cases, it was always a step or two ahead of him, laying the canvas on which he was expected to speak and be seen. Even in death, fresh artistic productions and discussions about his sexual identity continue to rival discourses about his writing prowess. However, the influential writer was not unaware of the lingering tensions between his sexual identity and the aura and captivating power of his soul-searching words. The author provides readers with a clear vista and a world of deep insights into some of his private burdens in a touching and brilliant interview conducted 39 years ago by Jordan Elgrably. James Baldwin was a man of personal honesty who, blessed with enviable courage, talked about his uniqueness regardless of how he was defeated by what others had said of him. He was often saddled with divesting identities others had created around his topical works and raging personality.

The author told Jordan Elgrably: “I was in difficulties because of (Eldridge) Cleaver, which I didn’t want to talk about then, and don’t wish to discuss now. My real difficulty with Cleaver, sadly, was visited on me by the kids who were following him, while he was calling me a faggot and the rest of it. I would come to a town to speak, Cleveland, let’s say, and he would’ve been standing on the very same stage a couple of days earlier. I had to try to undo the damage I considered he was doing.”

James Baldwin, author of the critically acclaimed novels Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), Giovanni’s Room (1956), and Another Country (1962), was reflecting on the burden of his sexual identity in that interview published under “Art of Fiction No. 78” in The Paris Review magazine, issue 91, Spring 1984. In that classic interview, he also said, “the sexual-moral light was a hard thing to deal with. I could not handle both propositions in the same book. There was no room for it. I might do it differently today, but then, to have a black presence in the book at that moment, and in Paris, would have been quite beyond my powers.”

Thrust a microphone in front of Baldwin, and he was most likely to lead you around brilliant winding paths, first through the labyrinth of his works and creative processes and then finally towards the confusing maze of his private and confined world where he kept many secrets and had little willingness in leaving them there forever. He came out clean when it was unfashionable, yet his sexual identity remained a burden because not all agreed with him how he would have wished to be incorporated. He was troubled by “that myth of the sexuality of Negroes,” as he described it in the essay, “the black boy looks at the white boy.”

Even if not much, James Baldwin was bothered by his admission about his writings’ identity and how the world perceived his character and tempers. “You care about the reviews so that somebody will read the book. So, those things are important, but not of ultimate importance.” Elsewhere in the interview, James Baldwin makes an honest confession: “It could make one’s head spin, the number of labels that have been attached to me.” He adds: “And it was inevitably painful, and surprising, and indeed, bewildering. I do care what certain people think about me.” In one of his earliest essays, “the black boy looks at the white boy,” James Baldwin remarked: “I confided to Norman (Mailer) that I was very apprehensive about the reception of Giovanni’s Room, and he was good enough to write some very encouraging things about it when it came out.”

Identities in Nobody Knows My Name

But James Baldwin had written about his sexuality and the many questions around identities long before that explosive and meaningful 1984 interview in the influential The Paris Review. Enter Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son, a 1961 book Dell Publishing Incorporated, New York published. The title of the book reflects Baldwin’s concern with his individuality, while the subtitle defines that distinctiveness as inborn and inimitable.

In a stirring introduction, the renowned novelist writes: “In America, the color of my skin had stood between myself and me; in Europe, that barrier was down. The question of who I was had at last become a personal question, and the answer was to be found in me. I think that there is always something frightening about this realization.” James Baldwin reeves up his batteries while writing about issues that troubled him all his life in this book of mind-piercing essays. The author begins the first piece with the classic words of Henry James, ‘”It is a complex fate to be an American.”‘

The opening lines of the essay, “The Discovery of what it means to be an American,” clearly highlight the author’s unease with an identity he was struggling with. Baldwin writes, briefly stepping away from Henry James, “We were both searching for our separate identities. When we had found these, we seemed to be saying, why, then, we would no longer need to cling to the shame and bitterness which had divided us so long.” Elsewhere, he notes: “a man may become uneasy as to just what his status is,” and then submits that, “a man can be as proud of being a good waiter as of being a good actor, and in neither case feel threatened. And this means that the actor and the waiter can have a freer and more genuinely friendly relationship in Europe than they are likely to have here.”

The first essay in Nobody Knows My Name references identity and color in a way that clearly shows that James Baldwin was alarmed by labels or status and their interpretations from very early on in his writing career. But this is not troubling. The author indicated the directions of his intellectual commitments in the book’s introduction by writing that “the question of color takes up much space in these pages, but the question of color, especially in this country, operates to hide the graver questions of the self.” In the essay “East River, Downtown: Postscript to a Letter From Harlem,” Baldwin writes: “There was not, no matter where one turned, any acceptable image of oneself, no proof of one’s existence. One had the choice, either of ‘acting just like a nigger’ or of not acting just like a nigger-and only those who have tried it know how impossible it is to tell the difference.” Without a doubt, James Baldwin was troubled by color and sexual identities. He was eager to cross the boundaries of identities, whether sexual, racial, or otherwise.

Unless readers, critics, and reviewers come to satisfying terms with the fact that James Baldwin didn’t want to die with a burdened heart, they may not fully grasp the beauty and kindness in his many controversial and stimulating texts. Many people continue to miss several fine points in their study of the man’s extraordinary literary, political, and intellectual genius because they fail to appreciate his burdens, and the “stigma and danger” that he faced. The world placed so many needless identities on one of America’s and the world’s greatest writers, but he did his best to release some of them and express his gentle humanity. One of the many burdens of being a Negro was that James Baldwin was often explaining things, and himself too. The world expected him to clarify his triumphs as if he wasn’t meant to excel. We can only continue to argue if he succeeded or not.