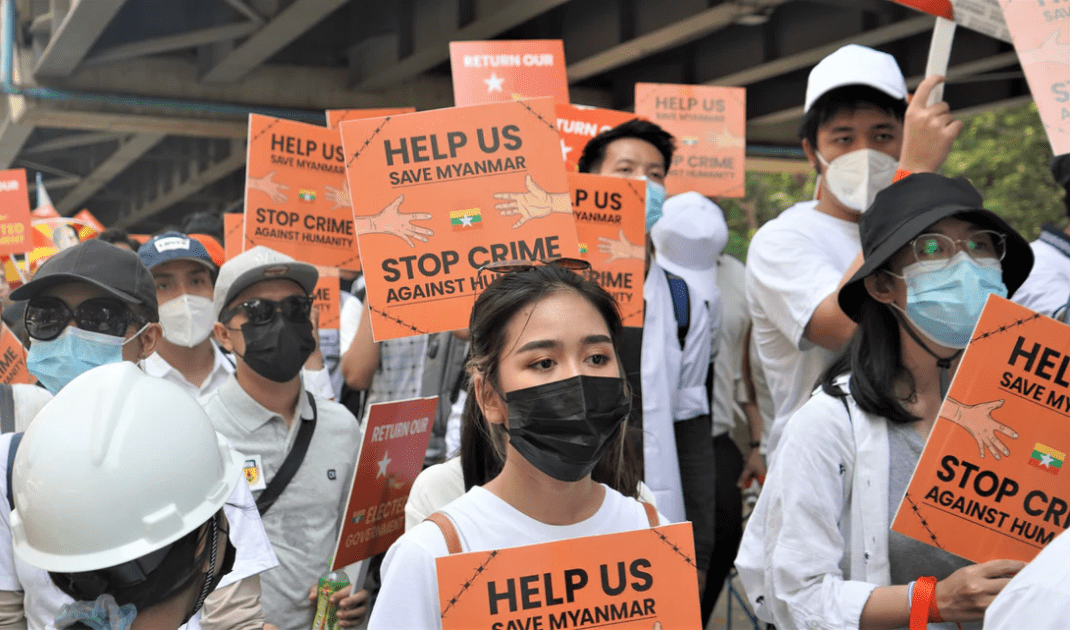

CNN Says Myanmar is a Prison, is this true?

By Steve Ogah

As a creative writer, one is constantly finding interest in the prison metaphor and its deployment in literature and factual living. This is one of the themes I committed myself to in “Campus Act”, a short fiction written some years back. I returned to this preoccupation in The African New Yorker, which is a collection of short stories. Here, I interrogated detention and loss of freedom in “Downtown Incidents.” In my book, Sowore: A Life of Political and Social Engagements, one took the view that the publisher of www.saharareporters.com , activist and politician; had found his prison and his relentless activism may be read in the light of one who is only trying to execute a prison break, figuratively speaking. Contemporary African writers are also busying themselves with the prison and its representation in fiction. For instance, Helon Habila’s 2001 Caine Prize winning short story, “Love Poems,” is set in prison during Nigeria’s past military regimes, particularly the ones during the 90s. In fact, Habila published a collection of short stories, Prison Stories (2001). The prison metaphor has now been used to depict the situation in Myanmar. This again, has excited one’s intellect. It is only appropriate, against the background of one’s literary preoccupation, to examine its deployment and see if one can view that frightening symbol in another direction vis a vis the rest of the world and Burmese.

Does CNN’s recent use of the prison metaphor, for the ongoing political conditions in Myanmar allow us to characterize Myanmar as Country as Prison, while the rest of us are freed people? Is this representation which appeared in the company’s Meanwhile in America newsletter of 16 November 2021, appropriate and does it exonerate the rest of us? But how did CNN arrive at its own stirring symbol?

“The Country is again a vast prison for its 54 million people.” That was how adroitly the cable news network characterized post-military coup conditions, before going further to insist that, “other than getting a few foreign passport holders out, there’s little sign the outside world can or will do much about it.” This is a frightening characterization for our shared humanity. This is more so because only recently on August 04, 2020, Naomi Fry, while writing in The New Yorker Magazine, reminded us that, “no struggle can take place alone.” She was reviewing Matt Ritt’s 1979 drama, “Norma Rae.” Why then is the rest of the world not applying enough pressure to force the coup plotters to respect civil liberties and return the country back to the path of participatory democracy? But this is not the first time that Myanmar will be in the news for all the wrong reasons.

Writing in The New York Times in its International Edition of March 3-4, 2018; Nicholas Kristof offered his opinion and warned of the “Slow-Motion genocide” in the state of Rakhine. But it now seems much of the world left Rohingya alone to their struggles. The senseless slaughter of a predominantly Muslim population went on without let or hindrance. And now, the world seems poised to allow citizens of this seemingly troubled country march to the barricades alone. Why are obtaining realities gloomy and the forecast, depressing? Answers are not crystal clear at the moment. But perhaps, Myanmar doesn’t account for much in world diplomatic and economic circles. Nothing is absolute here.

Returning to the questions at the head of this article, one must now maintain that If Myanmar is imprisoned, the rest of the world is vicariously imprisoned, shackled by its inabilities to act adequately and save the day in a deeply traumatized country. The strictures imposed on the rest of the world are by world political and economic powers with huge resources, but lacking the will to rapidly change things for good in Myanmar in the face of freedom dying a slow and painful death. Democracy died earlier.

In The Man Died, the Nobelist; Wole Soyinka, reminds us that, “the man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.” The rest of the world must therefore not sit back and watch the light of democracy die finally in Myanmar. We must collectively join hands and voices to erase CNN’s “little sign” phrase. Conversely, this article takes the view that there is a prison in every citizen in Myanmar, rather than the country being a prison. And this brings to mind, the writings of Ken Saro-Wiwa, who writing in Pita Dumbrok’s Prison, says that: “there is a prison in each of us. Each man’s responsibility is to find his own prison, then break out if it.”

Burmese must first break out from their own inhibitions individually, and then collectively; only then can they be free from their current tormentors. Otherwise, the country may just remain what CNN calls her. I sense an undercurrent of helplessness in the way CNN has framed the situation in Myanmar. But this need not be so. In the days to come, the rest of the world must not continue to ignore Myanmar. But if she does, it is only then that one would paraphrase CNN: the world and its 7.7 billion inhabitants are once again in a prison, and have failed to adequately rescue the situation in Myanmar.

Steve Ogah, is a Creative Writer and author of Barack Obama’s Logic. He is active on LinkedIn.www.linkedin.com/in/steveogah

Photo(C) Gayatri Malhorta@gayatrim16.

Featured Image:(C) Saw Wunna