Extraordinary Rendition and the Dangerous Precedent Set in Venezuela

- TDS News

- Trending News

- January 4, 2026

By: Donovan Martin Sr, Editor in Chief

What makes extraordinary rendition so dangerous is not only what it does to the person seized, but what it does to the system that claims to be governed by law. Extraordinary rendition is the act of a state capturing an individual outside its borders and transferring them without judicial process, without extradition hearings, without oversight by independent courts, and often without transparency. It replaces law with discretion. It replaces procedure with power. And once it is normalized, it quietly redefines what justice means.

The international system was built to prevent exactly this kind of unilateral action. The rules are simple in principle even if messy in practice: states do not seize people on foreign soil without consent, heads of state are not abducted, civilians are not killed without due process, and military force is not used to dictate political outcomes in other countries except under the narrowest, clearly defined circumstances. These rules exist not to protect bad actors, but to protect the world from chaos. They are guardrails, not rewards.

When those guardrails are removed, the consequences cascade. Extraordinary rendition does not remain a tool aimed at one villain. It becomes a precedent. It tells other governments that law is optional if you are powerful enough, that borders are negotiable, and that sovereignty is conditional. Once that message is sent, it cannot be unsent.

This is where Venezuela stops being the story and becomes the example.

If a state can seize a foreign leader, kill alleged criminals without trial, and announce that it will determine how another country is governed, then the distinction between enforcement and occupation collapses. Power vacuums follow because legitimacy collapses. Institutions fracture because no one knows which authority will survive. Ordinary people pay the price because instability always lands on those with the least protection.

But there is another layer that cannot be ignored, and it turns the lens inward.

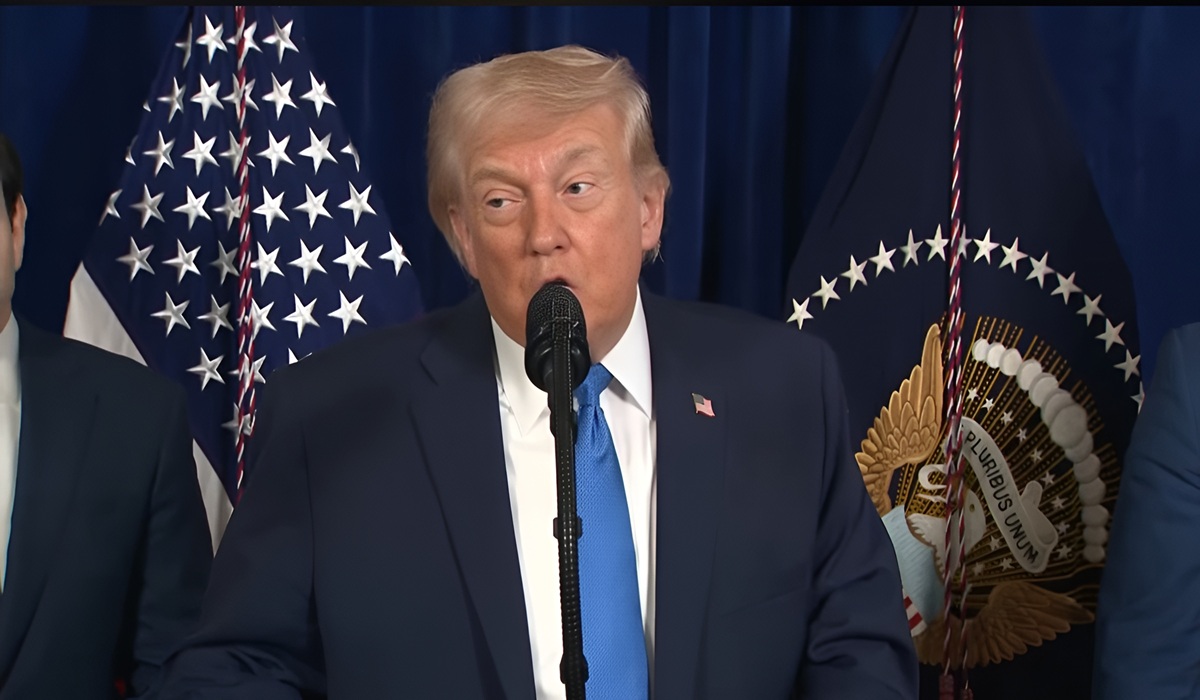

A functioning democracy is not defined only by elections. It is defined by constraint. It is defined by whether power is limited, whether branches of government restrain one another, and whether no single individual can act as judge, jury, and executor of national policy. When a president repeatedly bypasses Congress, acts unilaterally, and relies on the unquestioned obedience of the military because of his position as commander-in-chief, the question is no longer theoretical. It is structural.

If Congress is sidelined.

If oversight becomes performative.

If decisions of war, seizure, and governance are made without legislative authorization.

If the justification is simply “I can.”

Then democracy is no longer operating as designed.

The danger here is not one president or one party. The danger is normalization. Once unilateral action becomes routine, future leaders inherit not just the office, but the expanded power. What one president does in the name of urgency, the next will do in the name of necessity. And eventually, restraint becomes weakness, not virtue.

Supporters may argue that decisive action proves strength. But strength without accountability is not democratic strength. It is executive dominance. And history shows that systems built on dominance do not self-correct easily. They escalate. They overreach. They invite retaliation abroad and repression at home.

This is where the hypocrisy becomes unavoidable. If another nation kidnapped a U.S. president, killed alleged criminals without trial, and declared it would run America from abroad, the response would be immediate and absolute. It would be called an act of war. No American would accept “context” as a justification. No one would argue that America’s flaws made it fair. Sovereignty would suddenly matter again.

That is the standard that exposes the truth.

If it is unacceptable when done to the United States, it is unacceptable when done by the United States. Law cannot be situational. Democracy cannot be selective. And international rules cannot exist only when they are convenient.

The most unsettling part is this: actions like these do not make Americans safer. They make the world more volatile. They encourage other nations to adopt similar doctrines. They place U.S. citizens, businesses, and interests at greater risk abroad. They accelerate global fragmentation. And they weaken the very legal and moral foundations the United States relies on to protect itself in the long run.

You can oppose corruption.

You can oppose authoritarianism.

You can oppose criminal networks.

But when the response abandons law, bypasses democratic restraint, and concentrates power in one office, the cure begins to resemble the disease.

That is why this matters.

That is why people should be alarmed.

And that is why the question is no longer only about Venezuela.

It is about whether rules still govern power — or whether power has decided it no longer needs rules.