From Charity to Chaos: Why Boxing Day Turns Ugly Every Year

- Ingrid Jones

- Trending News

- December 26, 2025

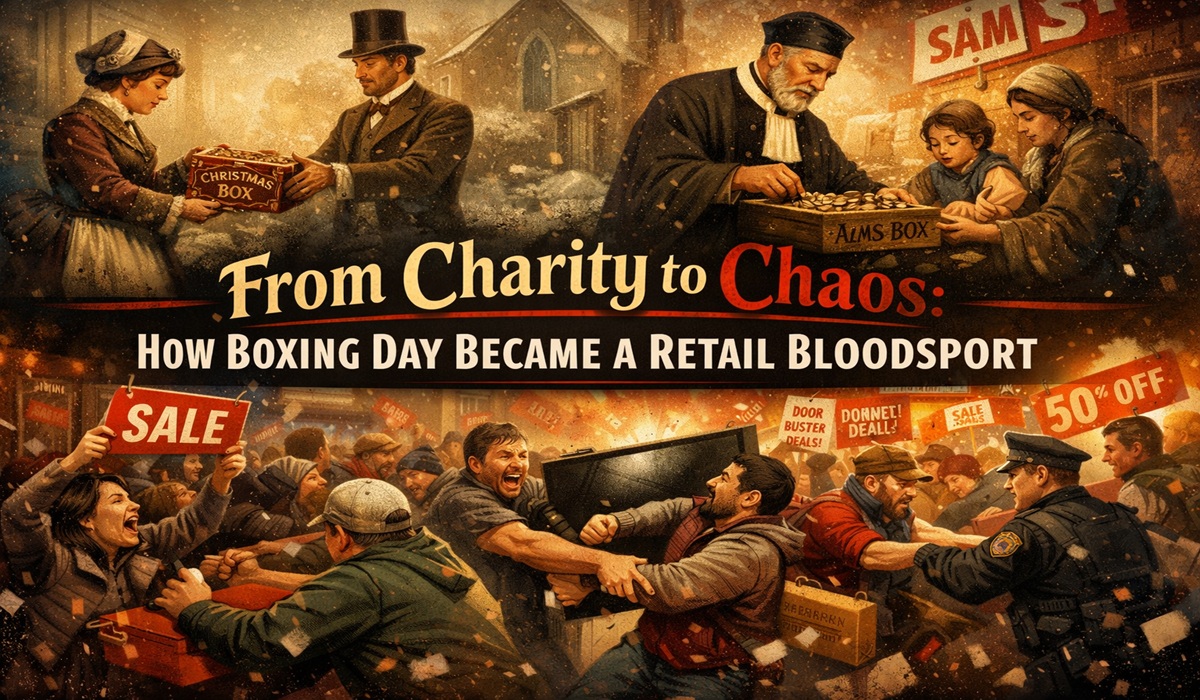

Boxing Day didn’t start as a shopping frenzy at all. Its origins are surprisingly quiet, practical, and even charitable.

Historically, Boxing Day dates back to Britain in the Middle Ages and early modern period. December 26 was the day when churches opened their alms boxes—literal boxes filled with donations collected during Advent—and distributed the contents to the poor. At the same time, wealthy households gave their servants the day off and sent them home with “Christmas boxes”: small gifts, leftovers, or money as thanks for the year’s work. It was a release valve after Christmas Day, a moment of generosity once the formal celebrations were over. That’s the “box” in Boxing Day.

For centuries, that was essentially it. No crowds. No door-crashers. No chaos.

The modern version is a completely different creature.

What changed was industrial capitalism, mass retail, and consumer psychology. As department stores expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Boxing Day became a convenient date to clear excess inventory after Christmas. Unsold goods took up space, cost money to store, and lost value quickly. Discounting made business sense. Over time, the sales became institutionalized, advertised, and eventually expected.

That’s where the “every year the same thing happens” part comes in. Boxing Day isn’t just a sale anymore—it’s a ritualized economic event.

People behave predictably because the system is designed to make them behave that way.

Retailers use a mix of scarcity and urgency to trigger strong emotional responses. Limited quantities (“only a few available”), time pressure (“one day only”), and steep headline discounts activate fear of missing out. Even when only one or two units of a heavily advertised item exist, the perception of opportunity is enough to pull people through the doors. Once inside, most shoppers don’t leave empty-handed. That’s the point. The loss-leader item is bait; the rest of the store is profit.

Long lineups and overnight waits aren’t really about the product. They’re about perceived advantage. Being first feels like winning. Humans are deeply competitive when resources appear scarce, even if that scarcity is artificial. Add social proof—news footage, viral videos, crowds lining up—and the behavior reinforces itself year after year. People don’t want to be left out of what looks like a mass opportunity.

There’s also a psychological crash after Christmas. People have spent weeks being told that buying equals caring, that gifts equal love, and that joy is something you can purchase. Once Christmas ends, there’s often regret, boredom, or a sense of “unfinished business.” Boxing Day sales offer redemption: this time I’m saving money, this time I’m being smart. The hunt becomes the reward.

As for the fights, injuries, and chaos, those are the extreme edge of the same mechanisms. Crowds + scarcity + stress + money + entitlement create volatility. Most people don’t go looking for conflict, but in packed environments where people feel they’ve “earned” a deal through waiting or sacrifice, frustration escalates quickly. When expectations aren’t met—when that hyped item is gone, or never really existed—anger fills the gap.

Why do people keep doing it?

Because the system works on human nature, not logic.

People aren’t just buying TVs or shoes. They’re buying the feeling of getting ahead, of beating the system, of not being the one who paid full price. Retailers know this. That’s why the cycle repeats annually with near-perfect reliability. The marketing language changes. The products change. The psychology does not.

Ironically, Boxing Day began as a day of giving and rest after Christmas. Today, it often becomes a test of endurance, patience, and impulse control. Same date. Same behavior. Different meaning.

And until scarcity, hype, and identity stop being profitable tools, the spectacle will keep returning every December 26—right on schedule.