Protest songs have never been just music, and they were never meant to be. They are emotional documentation, written in real time by people who can feel a nation turning. They show up when official language starts sounding hollow, when the news feels unreal, and when everyday people need something that tells the truth without permission. In those moments, a song can do what speeches cannot do. It can carry grief, anger, courage, and clarity in a way that lands instantly, even when the listener has no words of their own.

From the 1960s onward, protest music became one of the most recognizable cultural responses to turmoil in North America. It shaped public feeling during the Civil Rights era, during Vietnam, during the assassinations and political chaos of the late 60s, and during the long aftermath when people had to live with what the country had become. Those songs were not just background noise to history, they were part of history. They spread through radios, jukeboxes, house parties, campus rallies, union halls, and city streets, becoming a kind of shared conscience for people who felt powerless against forces far larger than themselves.

The 1960s in particular produced protest music that is still referenced today because it was born in a time when the stakes were brutally clear. The Civil Rights movement was fighting for basic dignity and legal equality in a country where segregation still shaped daily life. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. pushed a disciplined philosophy of non-violent resistance that was not rooted in softness but in strength. It was a refusal to surrender moral authority, even in the face of violence, intimidation, and the machinery of the state being turned against peaceful citizens. The songs that rose from that era carried a truth that is still uncomfortable to admit, which is that “order” has often been used as an excuse to crush dissent, rather than a promise to protect the public.

By the 1970s, the tone shifted. The Vietnam War was no longer an abstract issue for many families, it was a wound that kept opening. Public trust was cracking, and the country was absorbing the reality that institutions could lie with confidence and continue operating as if nothing had happened. Protest songs in that decade didn’t always sound hopeful, and they weren’t always trying to be inspiring. Many of them sounded tired, sharp, suspicious, or furious, and that was exactly the point. They reflected a nation wrestling with the fact that the people in power often survived scandals and failures while ordinary people were expected to pay the cost.

As the decades went on, the protest song never disappeared, it simply changed its clothing. In the 1980s, it adapted to a new era of economic pressure, cultural division, and global tension. In the 1990s, it lived inside music that challenged policing, inequality, hypocrisy, and the feeling that the system punished some communities more aggressively than others. In the 2000s, protest music took on another kind of urgency, shaped by wars abroad, fear at home, surveillance, and the expanding idea that security could justify almost anything. Protest songs became sharper again because the world was sharpening around the public, and people were trying to make sense of what was being done in their name.

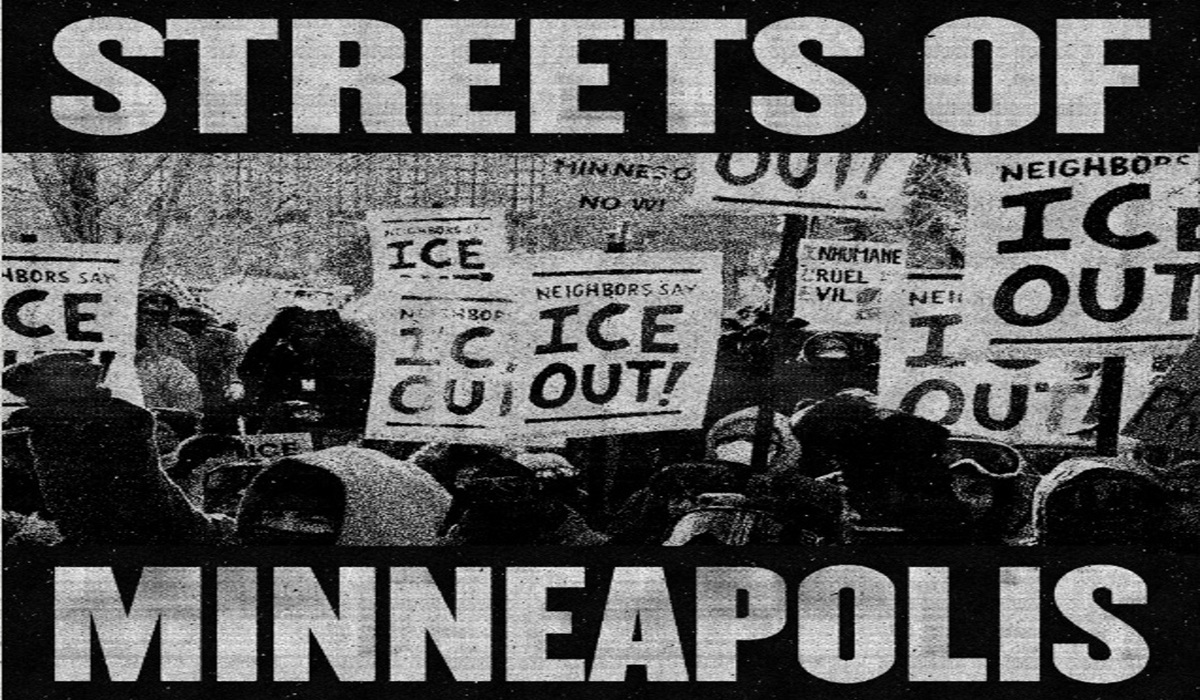

That is why it matters when a major cultural voice decides to speak now, not later, and not with a carefully staged press rollout. Over this past weekend, Bruce Springsteen released a song he says he wrote on Saturday, recorded the next day, and put out immediately in response to what he describes as state terror being visited on Minneapolis. He dedicated it to the people of Minneapolis, to innocent immigrant neighbors, and in memory of Alex Pretti and Renee Good. Even without hearing every note, the message is unmistakable. This was meant to be a response to a moment, and a warning to the country that history is beginning to rhyme again.

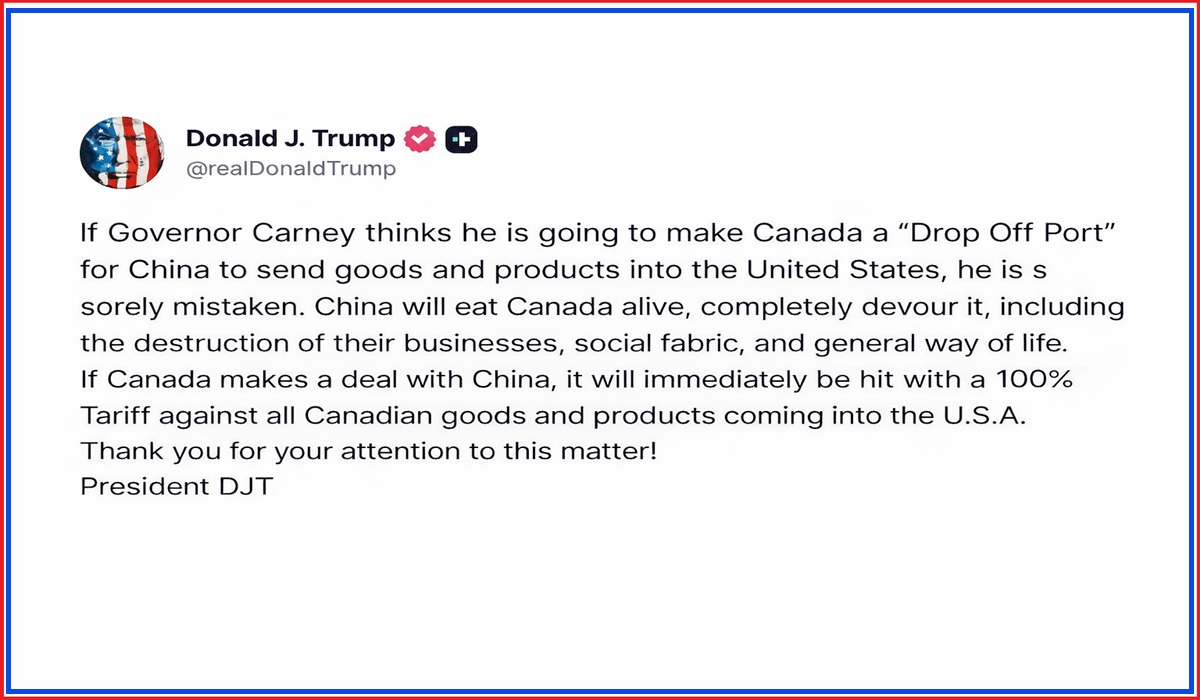

What makes the release hit harder is the sense that it is not about symbolism, it is about consequence. Springsteen framed it as a moral emergency connected to what he says is being permitted under the Trump administration through ICE operations. He described a reality of mass deportation, jailing, harassment, violence, and most recently, two murders in Minnesota. Whether people agree with his politics or not, the emotional argument is clear. This is not a debate about tone, it is a debate about what kind of country the United States is willing to become while the public watches.

There is a reason this song instantly calls to mind one of the most iconic protest tracks ever recorded, “For What It’s Worth” by Buffalo Springfield. Stephen Stills wrote it in 1966 after clashes surrounding Sunset Strip curfews, and it became an anthem far beyond that specific incident. It captured the atmosphere of a country feeling a crackdown, feeling tension in the streets, and sensing that something had shifted in the relationship between citizens and authority. The opening line is unforgettable because it is simple, but it is also chilling when it applies to the present. There’s something happening here, and people know it even when they cannot fully explain it.

That is the genius of great protest songs. They do not need to hand the listener a thesis statement. They do not need to scream their point like propaganda. They simply describe what it feels like to live inside a moment where power is tightening, where fear is spreading, and where normal life begins to feel unstable. When a protest song becomes timeless, it is usually because it names the emotion underneath the politics, and that emotion is almost always the same. People feel watched. People feel cornered. People feel like the rules are changing in a way that will not be applied evenly.

The truth is that America is not becoming a dark place for the first time. It has always carried darkness, and that darkness has always found ways to dress itself in language that sounds official, responsible, and necessary. That is why phrases like “law and order” can be so dangerous, because they can mean justice, but they can also mean domination. They can mean public safety, but they can also be a weapon that tells certain communities they are not safe at all. When the state begins to treat whole groups of people as threats by default, cruelty becomes easier to justify, and the public is trained to look away.

This is where ICE becomes central to the modern American protest story. For many people, it is not just an agency doing a job, it is the face of a system that has become more aggressive, more militarized, and more insulated from accountability. It is also the kind of force that can turn everyday life into a kind of quiet panic for immigrant communities, even for those who have done nothing wrong. When enforcement becomes a spectacle, it sends a message that goes beyond policy. It tells people who belongs, who doesn’t, and how quickly the ground can disappear beneath them.

That is also why non-violent movements matter now as much as they mattered in the 60s, and why they remain one of the most misunderstood forms of resistance. Non-violence is not weakness, and it is not compliance. It is discipline. It is strategy. It is the refusal to hand your opponent the excuse they are looking for. The reason non-violent movements have power is because they deny the state what it often wants most, which is a moment of chaos it can point to as justification for more force, more funding, and more repression.

It is easy to provoke violence. It is easy to bait people into a reaction. It is easy to push a crowd to the edge and then claim the fall proves the crowd was dangerous all along. That is why peaceful protest can be treated as terrorism so quickly, because the label does not need to be true to be effective. Once the label sticks, the public becomes easier to frighten, and frightened people will accept things they would never accept in calmer times. They will accept raids, surveillance, arrests, and crackdowns as long as they believe the target is someone else.

This is where protest songs do their most important work. They make it harder to lie, and they make it harder to pretend that nothing is happening. They remind people that fear is not the same as truth, and that silence is not the same as peace. They also remind people they are not alone, which is one of the biggest threats to any system that thrives on intimidation. When people realize they are not isolated, hate becomes less effective. When people realize their moral instincts are shared, the propaganda starts to crack.

Springsteen’s release fits into that tradition because it is not trying to be comfortable. It is trying to be honest, and honesty is rarely comfortable in moments like this. He is calling the country to account, and he is doing it in the language that protest music has always spoken best. It is the language of witness, the language of solidarity, and the language of refusal.

If there is a profound ending to this story, it is not the kind that comes as a poetic slogan, and it is not the kind that fades out with easy hope. The profound truth is that movements win when they refuse to become what power wants them to become. If the system is waiting for you to explode so it can justify crushing you, then disciplined peace becomes a form of protection and a form of power. If the system is trying to convince the public that compassion is weakness, then compassion becomes defiance.

The darkest times in any country are not only defined by what the state does, but by what the public accepts. That is why protest songs matter more than ever when the national mood turns ugly, because they remind people what they are hearing, what they are seeing, and what they are slowly being trained to tolerate. A protest song cannot stop a raid, and it cannot bring back the dead, but it can keep the conscience awake when the world is trying to put it to sleep.

And when conscience stays awake long enough, history stops belonging only to the powerful. It starts belonging to the people who stood still, stood together, and refused to surrender their humanity, even when everything around them was begging them to.