Image Credit, Heung Soon

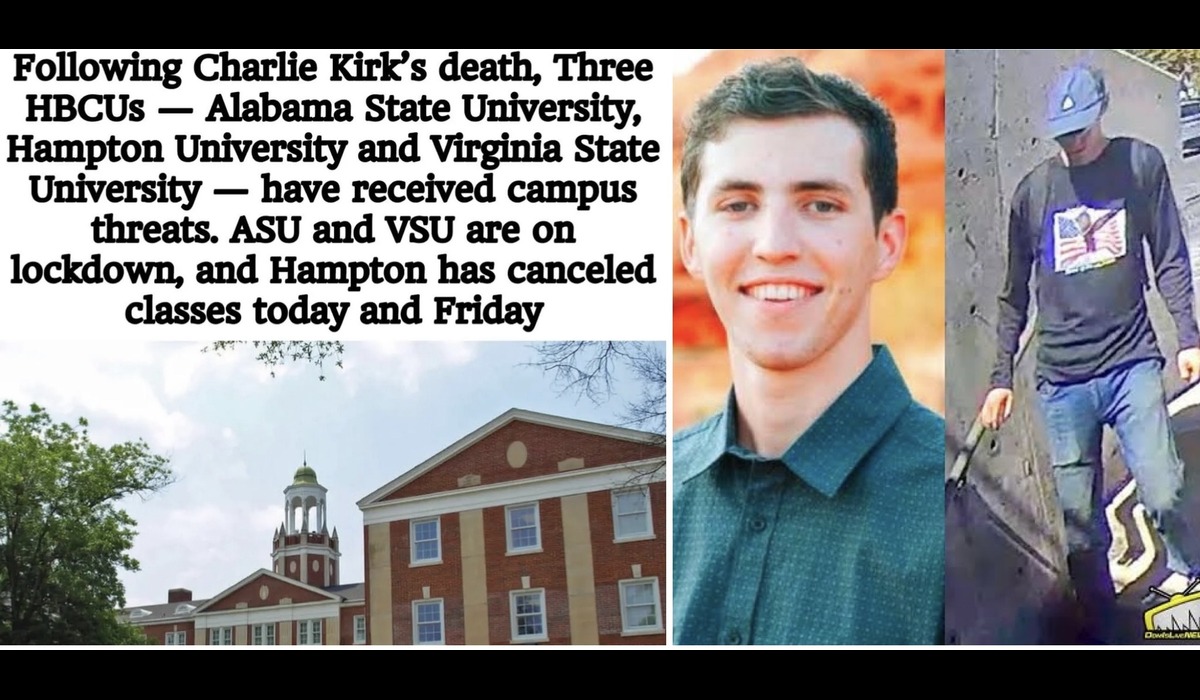

The spectacle that unfolded in Georgia shocked not only South Korean observers but also American industry leaders who had spent years cultivating trust with Seoul. More than three hundred South Korean workers—men and women who had arrived legally on proper working visas—were placed in chains by U.S. immigration officers in a sudden, highly publicized raid. The move was defended by President Donald Trump’s administration as a show of strength in immigration enforcement, but its underlying purpose was quickly revealed: to pressure South Korea’s president into committing $300 billion in new investments on American soil.

That figure is staggering—so staggering that it represents a demand far beyond what Seoul’s government could accommodate without tanking its own domestic economy. South Korea had already pledged and begun deploying tens of billions into the Georgia battery plant project, an investment hailed as one of the most significant examples of Asian capital fueling American manufacturing growth. The message from Seoul was clear after the arrests: the existing plant will be completed, but any talk of new projects or expanded investment is off the table.

What was meant as a show of force may instead prove to be an act of economic self-sabotage.

South Korea is not just any foreign partner. It is a treaty ally, a linchpin of U.S. strategy in East Asia, and one of America’s most dependable trading partners. To subject its citizens—legally working citizens—to shackles was not only humiliating but insulting on a diplomatic level.

The fallout was immediate. Georgia’s Republican governor, a staunch Trump ally, is now preparing an emergency trip to Seoul to attempt damage control. His mission is simple: convince South Korea’s leadership that the state values their investments and that this episode does not represent the true spirit of U.S. partnership. But the optics are brutal. It is a governor, not the federal government, who is now tasked with cleaning up after a presidential stunt.

Meanwhile, Canada, sensing opportunity, has intensified discussions with South Korea about redirecting some of its future investments northward. For Ottawa, this is not just about luring capital; it is about stepping into the role of a trusted partner precisely when Washington is undermining itself.

President Trump has long fashioned himself as the consummate dealmaker, the businessman who could out-negotiate anyone. But this episode underscores what many economists and diplomats have argued for years: coercion and humiliation are not negotiation strategies; they are acts of hostility.

The demand for $300 billion was not grounded in any formal trade framework or mutual economic benefit. It was a shakedown—an attempt to use immigration enforcement as leverage to extract money. Such tactics may resonate with a political base eager to see toughness displayed, but they are disastrous in the boardrooms where long-term investment decisions are made.

South Korea’s decision to halt further expansions is not simply about national pride; it is about risk management. Why would any government or company commit tens of billions more if the rules of the game can change overnight at the whim of a single U.S. politician?

The damage is not confined to diplomatic circles. On the ground, U.S. farmers and manufacturers are already feeling the pinch of Trump’s broader trade wars and erratic economic policy. The soybean industry, once a reliable export powerhouse, has seen crops rot in silos as China and other major buyers turned to alternative suppliers. Meat producers have faced similar barriers, watching valuable markets close while domestic demand remains insufficient to absorb the excess.

Now, with South Korea pulling back, another critical stream of capital and job creation is under threat. The battery plant in Georgia is still proceeding, but without further projects, the anticipated boom in ancillary industries—suppliers, logistics, research and development—will stall. Instead of a flourishing new industrial hub, Georgia may be left with a single facility and the bitter aftertaste of what might have been.

The irony is glaring. Trump’s core supporters, many of them farmers and workers in manufacturing-heavy states, are the ones paying the price. The tariffs he once boasted would bring in “billions and billions” have functioned instead as taxes on American consumers and producers. The markets he has alienated are not easily won back.

The semiconductor and advanced battery sectors illustrate the long-term risks of this kind of governance. America is engaged in a high-stakes race with China for technological dominance in chips and energy storage. South Korea, home to giants like Samsung and LG, is not a mere participant—it is a leader in these fields.

By antagonizing Seoul, Washington undermines its own strategic goals. Instead of deepening cooperation to secure supply chains, the U.S. has introduced distrust. The battery plant should have been a cornerstone of mutual technological advancement; now it is a reminder of how quickly political theater can upend economic logic.

Diplomacy is not only about dollars and factories. The way allies are treated sends signals around the world. If South Korea can be strong-armed and humiliated, what does that mean for other partners in Europe, Asia, or Africa? Why should they commit resources or align with U.S. interests if they fear being treated as pawns in a domestic political drama?

Canada’s quiet maneuvering with Seoul is instructive. Where Washington applied handcuffs, Ottawa extended a hand. It is an image that will not be lost on other governments looking to diversify their partnerships. In the long run, the United States risks ceding soft power not to rivals like China alone, but to its own allies who appear more dependable.

What is perhaps most remarkable is the blindness to consequence. The arrests of South Korean workers may have thrilled certain political rallies, where images of shackled foreigners play into narratives of sovereignty and control. But in the global economy, such images reverberate differently. They tell multinational companies that contracts and visas do not guarantee safety. They tell allies that loyalty does not protect them from humiliation.

The farmers who cannot sell their soybeans, the workers who will not see promised factories built, the local economies deprived of investment—these are the Americans who pay. Yet within Trump’s inner circle, the narrative remains one of strength, of forcing others to bend to America’s will.

The truth is that America has more to lose than South Korea. Seoul can redirect its capital. It can deepen ties with Canada, with the European Union, with Southeast Asia. But the United States cannot so easily replace what South Korea offers in technology, in capital, and in global strategic alignment.

The Georgia raid may prove to be one of those watershed moments historians look back upon—a point where a single political stunt crystallized the dangers of governing by impulse and intimidation. It is not simply that three hundred workers were placed in chains; it is that in doing so, the U.S. government placed its own economy and credibility in shackles as well.

The governor of Georgia’s upcoming trip to Seoul may salvage something, but the damage is done. Trust, once broken, does not easily return. Canada’s gain may be America’s loss. And the supposed “greatest dealmaker” may once again have proven that bluster is not business, and that humiliation is not negotiation.

The American economy, already strained by fractured trade relationships and battered agricultural markets, cannot afford many more such stunts. Yet if this episode is any indication, the lessons may not be learned until the costs are too obvious to deny.