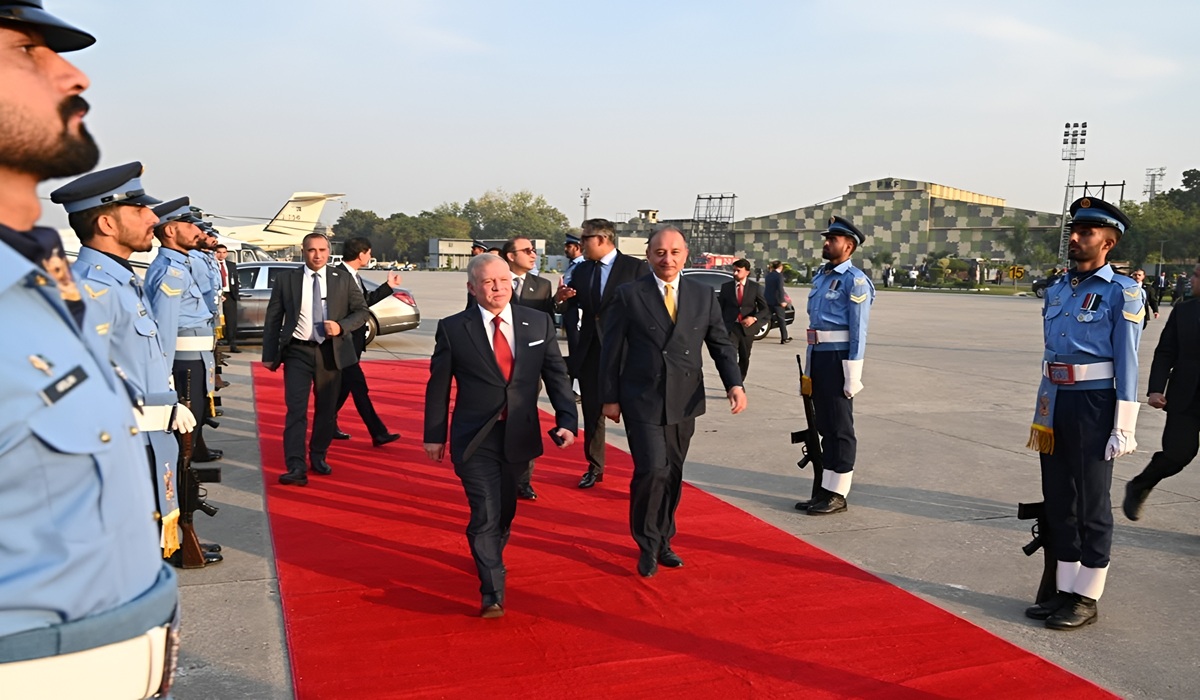

Image Credit, Army Amber

The year 2030 is not far, yet it promises to be dramatically different for Pakistan — politically, strategically, economically, and socially. One of the most decisive developments shaping this future is the appointment of General Asim Munir as Pakistan’s first Chief of Defence Staff (CDS). His role marks a fundamental reorganization of the defence structure and sets the stage for major changes in Pakistan’s security landscape, civil–military relations, and regional posture.

This column evaluates how Pakistan will look like in 2030 under the CDS model, what Asim Munir’s vision may achieve, whether he can establish exemplary norms for future military leadership, the prospects of eliminating terrorism, and whether Pakistan’s armed forces can emerge as the strongest and most agile force in the region.

The creation of the CDS post represents a bold transformation in Pakistan’s defence management. By 2030, this office is expected to evolve into the nerve center of national security planning. Instead of three forces working in silos, Pakistan will have: integrated defence planning, joint operations command,

unified procurement and logistics, cyber and space-based strategic units and centralized intelligence coordination.

This institutional harmony can reduce duplication, quicken decision-making, and strengthen precision response during crises.

With General Asim Munir at the helm, this structure is likely to emphasize operational discipline, financial transparency, and a modern defence outlook aligned with global standards.

Asim Munir is known for calm discipline, moral clarity, and a strong emphasis on institutional integrity. His long-term vision for Pakistan by 2030 may include: Pakistan’s transition to joint command could revolutionize how the military fights, trains, and prepares. Coordinated air, naval, and land strategies will reduce reaction time and improve accuracy during operations. Munir’s background as DG ISI and MI indicates a leader who understands intelligence deeply. By 2030, Pakistan could have a unified intelligence grid that eliminates blind spots and improves counterterrorism efficiency. A CDS with a clear constitutional mandate may actually reduce political friction and restore healthy boundaries between civilian leadership and the military — a step essential for Pakistan’s democratic maturity. If Munir embeds these values today, they will become the guiding principles of Pakistan’s defence management for decades.

As the first CDS, Asim Munir is not only shaping policy — he is defining the office itself. The standards he establishes in the present could become the unwritten commandments for future defence leadership.

These norms may include: zero tolerance for corruption within defence institutions, improved civil oversight on defence expenditure, a depoliticized military hierarchy,

integrated academies for joint training, advanced cyber defence protocols, enhanced disaster relief roles and respect for constitutional limits. If maintained, these reforms can create a cultural shift — a military that is strong yet restrained, modern yet constitutionally aligned.

The expectation that Pakistan will completely eliminate terrorism by 2030 is idealistic but not impossible. However, full eradication depends on multiple internal and external factors.

Instability in Afghanistan, foreign-sponsored terrorism, radicalization within society, economic hardship and youth frustration, and border management complexities are

challenges that will continue.

Militancy will be dramatically reduced. Terror cells will face severe operational limits.

Intelligence capabilities will be stronger than ever. Urban terrorism may decline significantly. Border security will become more technologically driven likely scenario in 2030. Pakistan may not achieve absolute peace, but it can create a secure environment where terrorism becomes an exception — not a defining national problem.

By numerical strength and budget, overtaking India is not feasible. But Pakistan can emerge as: the most agile force, the most joint and integrated force, one of the best trained militaries, a powerful missile and tactical deterrent state and a rising cyber and electronic warfare power.

With modernization of the navy and expansion of Pakistan’s presence in the Arabian Sea, Pakistan can enhance its strategic relevance in the Indian Ocean. By 2030 Pakistan may not be the “largest” force — but it can become one of the most capable in the region.

By 2030, Pakistan may experience major transformation across multiple sectors: internal security, significantly reduced terrorism, stronger policing and intelligence,

safer major cities and rapid-response counterterror units.

More mature politics if civil–military balance improves stronger parliamentary committees on defence.

Pakistan’s stability will depend heavily on:

industrial modernization, digital transformation, regional trade corridors, energy diversification and foreign investment through Gulf and Chinese partnerships.

If political stability holds, Pakistan could enter a phase of sustained economic recovery. A younger, more tech-driven population, greater participation of women in workforce, rise in service-sector jobs and expansion of private education and health sectors.

A strong CDS structure will allow Pakistan to negotiate regional security matters confidently.

By 2030, Pakistan under the CDS model could be more secure, more integrated, and more strategically aware than ever before. General Asim Munir’s role as the first CDS gives him a unique opportunity to build new defence traditions, strengthen national security, reduce terrorism, and stabilize civil–military dynamics.

The real success will be measured not merely in military strength, but in whether Pakistan becomes a safer, stable, democratic, and economically vibrant country. If the CDS model works as envisioned, 2030 may become the beginning of a stronger, modern and confident Pakistan.