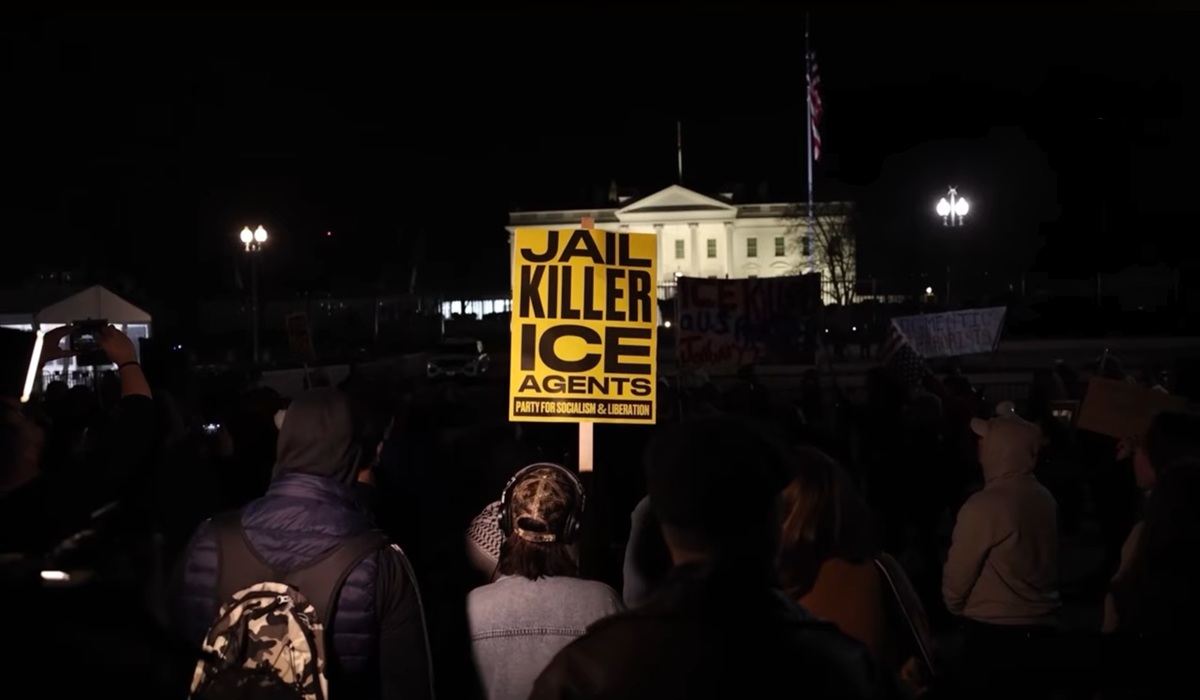

Image Credit: Mark Thomas

There are moments in a nation’s life when the air feels heavy—when decisions made in the polished corridors of power carry the weight of something irreversible. NSPM-7 is one of those moments. Cloaked in the language of “security,” “stability,” and “protecting democracy,” this presidential memorandum might one day be remembered not as a measure to safeguard America, but as the quiet legislative prelude to its undoing.

At first glance, the title sounds harmless, even noble: Countering Domestic Terrorism and Organized Political Violence. It reads as a necessary tool in an age of heightened tension, misinformation, and extremist threats. But behind that bureaucratic calm lies something far more chilling—a document that blurs the line between protection and persecution, between safeguarding democracy and controlling it. This is not a routine executive order. It is a radical reconfiguration of state power, one that hands the federal government an unprecedented reach into the hearts, minds, wallets, and digital lives of its own citizens.

The danger of NSPM-7 lies not merely in its intentions, but in its architecture. Its language is deliberately broad, its definitions dangerously vague. Words like “political violence,” “intimidation,” “disruption,” and “anti-American sentiment” are scattered through the text with alarming elasticity. In the wrong hands—and history tells us power eventually always falls into the wrong hands—these phrases can mean whatever those in authority want them to mean. They can be stretched, redefined, and reinterpreted to encompass anyone who dares to think, speak, or protest differently.

That is the essence of authoritarian lawmaking: to write the rules so that the state can never truly be wrong, and the citizen can never truly be right.

When NSPM-7 was announced, few outside Washington grasped the depth of its implications. Many still don’t. It was sold as an administrative framework—a way to unify agencies like the Department of Justice, the Treasury, and the IRS in combating domestic extremism. But its true design is far more insidious. It fuses financial surveillance, political monitoring, and legal enforcement into one seamless mechanism of control. It empowers federal agencies not only to investigate violence but to preemptively target those they believe might engage in it, including donors, nonprofits, and online communities.

This is where the slope turns steep and slippery. Because what defines a “threat” is no longer a matter of criminal evidence—it becomes a matter of ideology. Under NSPM-7, to hold views that challenge the prevailing orthodoxy could be seen as subversive, even dangerous. Dissent becomes conflated with extremism. Criticism of government policy becomes a potential security risk. Activists, journalists, and advocacy groups—anyone operating outside the state-approved narrative—suddenly find themselves in the crosshairs of “national protection.”

It is the kind of measure that would make Joseph McCarthy proud and George Orwell sigh in recognition.

What makes NSPM-7 so perilous is not just its content, but its timing. America stands at a crossroads of deep political polarization, social unrest, and public distrust. The fear of domestic instability is real—and fear, more than ideology, is the great enabler of authoritarianism. The more frightened a population becomes, the more it is willing to trade liberty for security, individuality for order, freedom for the illusion of safety. NSPM-7 feeds on that fear. It weaponizes the public’s anxiety and redefines loyalty through obedience.

For those who remember the early 2000s, the echoes of the PATRIOT Act are deafening. Then, too, the country was told it must sacrifice privacy and due process for the sake of protection. And then, too, the consequences came quietly—expanded surveillance, secret watchlists, the normalization of spying on one’s own citizens. NSPM-7 takes that legacy and internalizes it, turning the focus inward not on terrorists from abroad, but on Americans themselves.

The inclusion of agencies like the IRS and the Treasury Department in this directive is particularly ominous. They are not intelligence organizations. Their role here is financial control—tracking, auditing, and potentially freezing the resources of those deemed “associated” with domestic extremism. No trial. No conviction. Just suspicion, investigation, and economic suffocation. The state may not need to imprison dissenters if it can simply bankrupt them into silence.

And yet, the most dangerous part of NSPM-7 is not what it authorizes—it’s what it normalizes. Once a government claims the right to define extremism by ideology, democracy ceases to be a system of ideas and becomes a system of permission. The state no longer protects citizens’ rights; it decides who deserves them. Today it may target the far right, tomorrow the far left, and eventually anyone inconvenient to power. Once that gate is open, it never fully closes.

The philosophical undercurrent of NSPM-7 is deeply troubling because it redefines dissent itself as a form of disorder. It recasts political opposition as a form of violence. It frames questioning authority as a threat to national unity. This inversion of values is not accidental—it is the precondition of authoritarian governance. When law enforcement becomes ideological enforcement, democracy no longer dies in darkness; it dies in definition.

America was founded on the principle that government power must be restrained precisely because human nature cannot be trusted with it. NSPM-7 betrays that founding insight. It assumes that good intentions will govern bad tools, that a system designed for surveillance and control will never be misused. But power, once granted, is rarely ungranted. History offers no shortage of warnings. From the Sedition Acts of 1798 to the internment orders of World War II, every expansion of federal policing under the banner of safety has later been remembered as a moral failure. The danger now is that NSPM-7 may be remembered as something even worse—a structural one.

Consider the language that peppers its implementation notes: “anti-Americanism,” “anti-Christianity,” “hostility to traditional values.” These are not legal concepts; they are cultural judgments masquerading as law. Who decides what is “anti-American”? Who decides what is “hostile”? Once morality becomes a legal criterion, the rule of law collapses into the rule of opinion. And when opinion belongs to the state, justice becomes whatever power says it is.

This is the genius—and the horror—of NSPM-7. It does not need to announce itself as censorship; it only needs to make people afraid of being mistaken for a threat. It turns compliance into a survival instinct. People will censor themselves. Organizations will pre-screen their speech. Donors will quietly withdraw. And within a few years, the loudest sound in the public square will be silence.

There is also the constitutional question—one that cuts to the core of what it means to be an American. The First Amendment does not protect speech the government likes; it protects speech the government despises. It was written precisely because freedom is not a reward—it is a safeguard against tyranny. NSPM-7 tests that safeguard by erasing the line between speech and crime, between belief and behavior. It turns ideology into evidence.

Even the judicial system will struggle under this framework. How does one prove innocence when the alleged offense is not an action but an attitude? How does one contest a label like “extremist” when the evidence is classified or interpretive? NSPM-7, by design, sidesteps such questions. It shifts accountability from the state to the citizen, demanding that every American constantly prove their loyalty. It is not a system of justice—it is a system of suspicion.

And yet, for all its dangers, NSPM-7’s most frightening aspect may be its subtlety. It does not shout dictatorship. It whispers it. It wears the familiar language of democracy—freedom, safety, order—while draining those words of their meaning. It speaks in the tone of bureaucracy, not brutality. That makes it far more effective, and far more dangerous. Because people do not rise up against paperwork. They comply.

In the years to come, the real measure of NSPM-7’s damage will not be in arrests or prosecutions. It will be in what disappears quietly: the courage to dissent, the freedom to assemble, the confidence to speak. It will be in the journalists who avoid certain topics, the nonprofits that close rather than risk investigation, the donors who stop funding advocacy, the students who learn to stay silent in class. That is how democracy erodes—not with explosions, but with edits.

The tragedy is that America has seen this pattern before and still refuses to recognize it. The allure of security has always been democracy’s Achilles’ heel. From the Red Scare to the War on Terror, the government has repeatedly expanded its reach in moments of fear, and every time it has taken decades to recover what was lost. NSPM-7 is that story reborn—only this time, the target is not an external enemy. It is us.

What makes this memorandum one of the most dangerous in U.S. history is not only its potential for abuse, but its pretense of legitimacy. It does not need new laws or votes. It operates within existing frameworks, quietly reinterpreting them. It is authoritarianism by memo—a silent coup executed through language and procedure. And because it is wrapped in the rhetoric of national unity, opposing it can be portrayed as unpatriotic, even treasonous.

In moments like this, history does not whisper—it screams. It warns that liberty is never lost all at once, but piece by piece, policy by policy, until the people who once took pride in their freedom can no longer remember what it felt like to be free. NSPM-7 may be the latest chapter in that long erosion, and perhaps the most decisive one.

If America continues down this path—if it allows fear to justify surveillance, ideology to justify investigation, and obedience to replace citizenship—then the country that once declared independence from tyranny will have, through its own hand, reinvented it.

Democracy does not die when a dictator rises. It dies when citizens no longer recognize the moment they became subjects. And with NSPM-7, that moment may already be upon us.