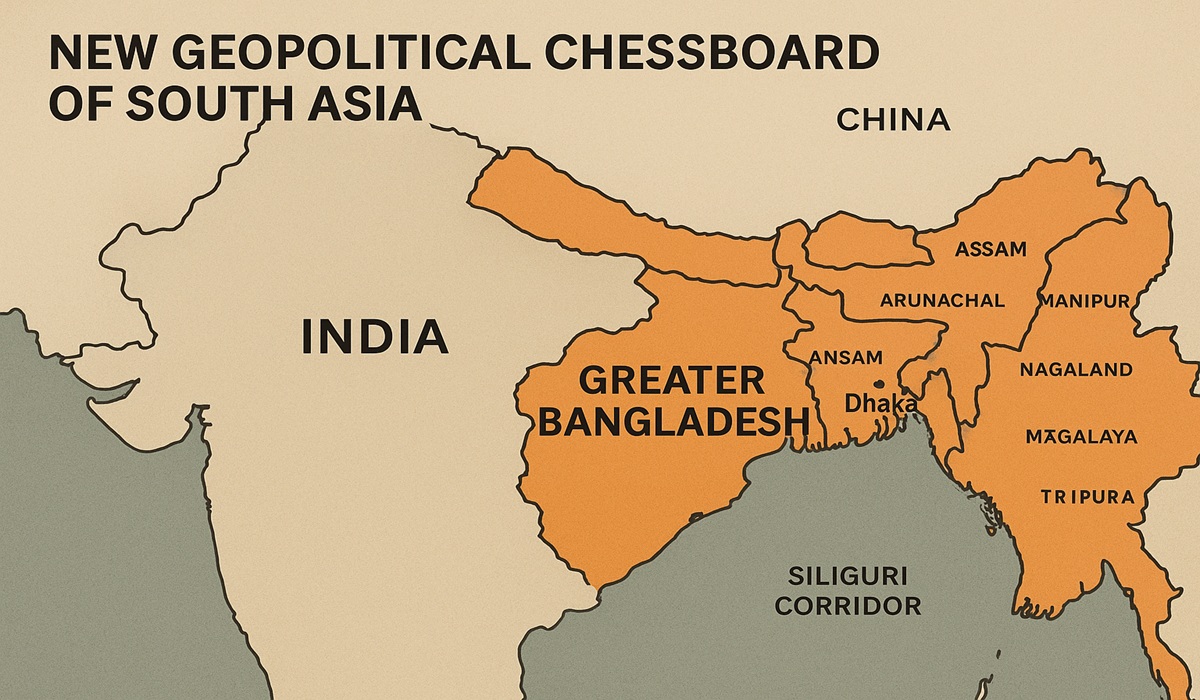

New Geopolitical Chessboard of South Asia

- Naveed Aman Khan

- Breaking News

- Middle East

- October 31, 2025

The geopolitical map of South Asia has long been a theater of historical grudges, strategic rivalries, and shifting alliances. Among the region’s most intriguing yet controversial possibilities is the concept of a “Greater Bangladesh” — a strategic framework that imagines the annexation or political integration of India’s Siliguri Corridor and the Seven Sister States Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura with Bangladesh. Though such an idea appears far-fetched, it holds fascinating implications for Pakistan’s regional policy and its long-standing contest with India.

The “Greater Bangladesh” concept represents more than just territorial ambition. It embodies a geopolitical counterbalance to Indian dominance — a potential strategy that could weaken India internally and create a multi-front diplomatic and security challenge. The idea, however hypothetical, has roots in the demographic, economic and political realities of northeastern India and Bangladesh’s evolving regional aspirations.

The Siliguri Corridor — often referred to as the “Chicken’s Neck” — is a narrow strip of land, only about 22 km wide, connecting mainland India with its northeastern states. It is one of the most strategically vulnerable point in India’s geography. Any disruption or control over this corridor would effectively cut off the Seven Sister States from the Indian heartland.

From Pakistan’s strategic viewpoint, encouraging instability or geopolitical realignment in this corridor could become a masterstroke in weakening India’s territorial integrity without direct military confrontation. Bangladesh’s proximity and cultural links with the region’s Bengali and tribal populations make it a more natural influencer in the area than Pakistan could ever be directly. Thus, Pakistan’s role would be one of indirect facilitation — through diplomacy, intelligence coordination, and leveraging shared economic interests with Bangladesh.

Bangladesh today stands as one of South Asia’s emerging economic powers, boasting steady GDP growth, industrial expansion, and an increasingly assertive foreign policy posture. While Dhaka has historically aligned with India for strategic convenience, a new generation of policymakers and citizens is questioning whether dependence on New Delhi truly serves Bangladesh’s long-term interests.

The northeastern states of India share cultural, linguistic, and religious ties with Bangladesh. Millions of ethnic Bengalis live across Assam and Tripura. These connections create a potential sociopolitical bridge that could, under certain conditions, encourage separatist tendencies and greater affinity toward Bangladesh rather than distant New Delhi.

Should Bangladesh ever seek to project influence across the Siliguri Corridor, it could do so under the pretext of protecting Bengali populations or promoting cross-border economic integration. This would not necessarily mean overt military annexation, but rather a gradual political and economic absorption — a strategy that could redefine the subcontinent’s borders more subtly than conventional warfare.

For Pakistan, the notion of a Greater Bangladesh is less about ideological support and more about realpolitik. The breakup of India in its northeast would serve Islamabad’s enduring strategic objective: to weaken Indian hegemony and create new regional dynamics unfavorable to New Delhi.

If Pakistan were to support Dhaka diplomatically and economically — through regional trade forums, intelligence cooperation, and global advocacy for minority rights in India’s northeast — it could strengthen Bangladesh’s position as an independent regional pole. This would be a psychological and diplomatic setback for India, which has long prided itself on being the region’s uncontested power.

A fractured India would force New Delhi to divert security resources to its eastern borders and internal insurgencies, thereby reducing pressure on Pakistan’s western front. Such a development could help Islamabad stabilize law and order in its own restive regions like Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan by diminishing external Indian influence and intelligence activity in those provinces.

Transforming the Greater Bangladesh vision into reality would require a combination of demographic leverage, economic interdependence, and geopolitical timing. Pakistan and Bangladesh could collaborate within broader Islamic or Asian multilateral frameworks, strengthening trade corridors and intelligence cooperation while jointly lobbying international forums about India’s alleged human rights violations in its northeastern states.

However, practical execution faces monumental obstacles. Bangladesh, despite its occasional friction with India, remains dependent on Indian transit routes, energy cooperation, and diplomatic goodwill. Its military and security apparatus have deep coordination with India’s. Dhaka’s ruling elites understand that a direct confrontation with India could endanger its own stability.

Pakistan’s ability to project influence into the Indian northeast is limited by geography and its own domestic priorities. While Islamabad can exploit diplomatic and ideological avenues, it lacks the logistical proximity to directly affect the Siliguri region. Thus, a Pakistan-Bangladesh alliance would primarily be political and psychological rather than territorial — aimed at keeping India perpetually insecure about its eastern flank.

Even the theoretical pursuit of a Greater Bangladesh would force India to recalibrate its security priorities. New Delhi would be compelled to reinforce its eastern military commands, potentially stretching its defense budget and weakening its focus on Pakistan’s western border. The resultant multi-front anxiety could lead India to overextend itself militarily and diplomatically — a classic example of strategic overreach.

In turn, Pakistan could use this window to consolidate its control over internal challenges in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, secure its borders, and reassert its regional narrative through soft power and diplomacy.

While the dream of a Greater Bangladesh may never fully materialize, its strategic implications are profound. For Pakistan, even entertaining this possibility strengthens its psychological and diplomatic leverage against India. It highlights how regional alliances and ethnic interconnections can subtly erode New Delhi’s sense of invincibility.

Ultimately, this concept underscores a timeless truth of South Asian geopolitics: borders here are not just lines on a map but reflections of history, identity, and power. Whether or not Pakistan and Bangladesh ever transform the dream into a reality, the mere notion of it keeps India on the edge — politically, militarily, and strategically.