Hostile Architecture in Paris, Tough Crackdowns in America: Which Offers More Dignity?

- TDS News

- Breaking News

- August 21, 2025

By: Donovan Martin Sr. Editor in Chief

Image Credit, Wiki and Paula Quiyahora

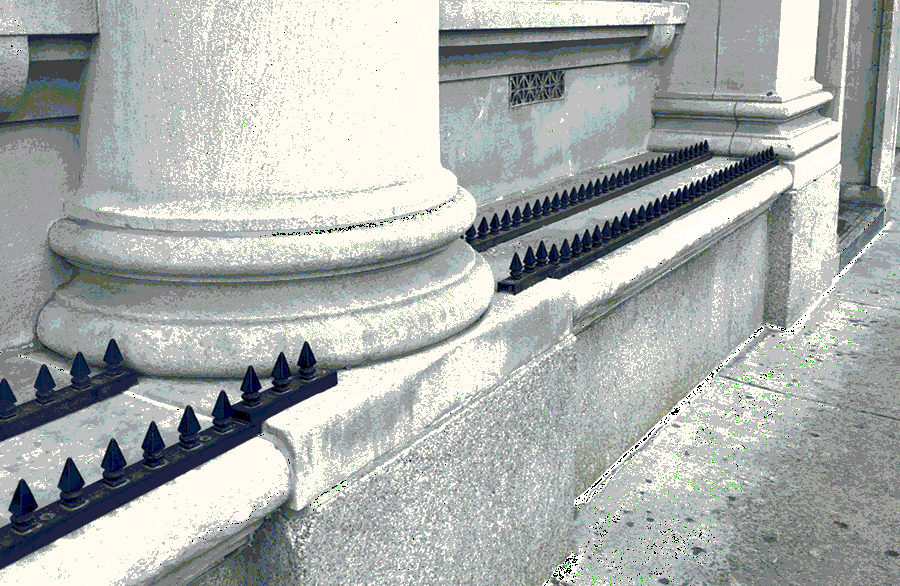

Walk through Paris long enough and you’ll notice something curious about its public spaces. The benches in its parks are divided by cold, metal bars that cut the seats in two. Ledges outside buildings are studded with rows of spikes. Under bridges, angled rails prevent anyone from lying down. To the casual passerby, these might look like odd design quirks. But they are deliberate. This is hostile architecture—a silent form of urban control, designed not to beautify or improve, but to exclude. Its message is clear: if you are homeless, there is no place for you here.

This kind of design has been spreading across global cities for decades. It doesn’t come with political speeches or press releases. It doesn’t arrest anyone. It simply makes the act of resting or sleeping in public so uncomfortable that people have no choice but to keep moving. In many ways, hostile architecture is society’s way of pretending homelessness does not exist. By making people invisible, it reduces the discomfort of those who have homes while deepening the suffering of those who do not.

Now, contrast that quiet cruelty with what’s unfolding across the Atlantic in the United States under President Donald Trump. His administration has taken a far more aggressive approach: dismantling homeless encampments, clearing tent cities, and forcing individuals into a stark choice. Stay in the streets and face arrest—or enter a government-run facility that promises food, shelter, and treatment. The policy is controversial, criticized by many as coercive, even authoritarian. Yet unlike the spikes and slanted benches of Paris, it acknowledges homelessness as a crisis and attempts to confront it directly, albeit harshly.

So which is worse: a silent system that pushes people into the shadows, or a loud, uncompromising crackdown that forces them into state care or jail?

Before weighing the two, it’s worth pausing on what homelessness actually is. It is not simply being without a house—it is being without safety, without privacy, without permanence. Life on the street is exposure to the elements, constant hunger, fear of violence, and the crushing isolation of being invisible to the rest of society. Mental illness and addiction often intertwine with these conditions, creating cycles that are extremely hard to escape without intervention.

To imagine sleeping outside during a Parisian winter, or under a freeway overpass in Los Angeles, is to understand that this is not a sustainable or dignified existence. It is survival in its rawest, most unforgiving form. This is why some argue that Trump’s model, however heavy-handed, is at least a recognition of reality. If the choice is between freezing on a sidewalk or entering a facility where one receives meals, medical attention, and shelter, then perhaps even a coercive system is preferable to abandonment.

Paris’s hostile architecture is, in many ways, the opposite approach. It doesn’t force people into shelters. It doesn’t even offer alternatives. It simply ensures that the most visible expressions of homelessness—sleeping in a public square, resting on a bench—cannot exist. For city officials, the appeal is obvious. Tourists don’t have to step around sleeping bags. Commuters aren’t confronted with the raw evidence of inequality on their way to work. The cityscape looks orderly, sanitized, curated.

But what happens to the individuals themselves? They are displaced from one street corner to another, never truly relieved of their suffering, only hidden. The problem is not solved; it is designed out of sight. This is why critics call hostile architecture a kind of cruelty disguised as cleanliness. It doesn’t even pretend to help. It simply erases the human being from the equation.

By contrast, Trump’s policies force the issue. Encampments are torn down. Law enforcement is present. Vans transport people to facilities. It is disruptive, sometimes traumatic, but undeniably visible. The message is not “you don’t belong here,” but rather “you must go here.”

Facilities vary in quality. Some are well-run, offering treatment for addiction, mental health services, and transitional housing programs. Others resemble warehouses—crowded, underfunded, and bureaucratic. For many individuals, being forced into such spaces can feel like imprisonment rather than rehabilitation. Critics argue that true dignity requires choice, and that forcing people into institutions strips away autonomy.

Yet for supporters of the policy, the calculation is different: dignity can begin with a hot meal, a clean bed, and freedom from the cold. Imperfect shelter, they argue, is still shelter. In this light, Trump’s crackdown is not about punishing homelessness but about refusing to accept it as an inevitable feature of American streets.

When you place the two systems side by side—Paris’s hostile architecture and America’s forced facility placements—both reflect a deeper truth: society struggles to confront poverty in humane and sustainable ways. Paris hides its homeless. America corrals them. Neither approach fully addresses the root causes: the lack of affordable housing, the collapse of mental health care, the opioid crisis, stagnant wages, and widening inequality. Yet both, in their own ways, reflect a refusal to simply let people exist indefinitely in the streets.

And here lies the uncomfortable question: is it more dignified to let someone remain free but unsheltered, or to compel them into shelter they may not want?

Critics of Trump’s policy are quick to emphasize its coercive nature. No one should be forced into an institution. Choice matters. Autonomy matters. And yet, the silent alternative—leaving people to sleep under bridges or designing them out of public spaces—raises its own moral contradictions. If we believe homelessness is unacceptable, then doing nothing is a form of neglect. Hostile architecture, in this sense, is not neutral—it is active abandonment, a way of preserving appearances while ignoring suffering. At least the American crackdown forces resources onto the table. At least it compels a reckoning.

But both approaches still miss the heart of the problem. Shelters and facilities are stopgaps. Studded benches are avoidance. What is needed is long-term investment in housing, community-based treatment, and a willingness to integrate rather than segregate those without homes.

Perhaps the most provocative point is this: many who criticize Trump’s crackdown are not themselves offering alternatives. It’s easy to condemn government overreach. It’s harder to open your own home, share your own meals, or take on the personal responsibility of sheltering a stranger. This doesn’t absolve governments of their duty, but it does highlight the limits of moral outrage when it isn’t accompanied by personal action. If hostile architecture is wrong, and if mandatory facilities are oppressive, then what is left? Who is willing to step in, personally, to bridge the gap?

Paris and Washington offer two very different models, both imperfect, both troubling. One hides its poor; the other corrals them. Both approaches force us to confront a central question about dignity, freedom, and responsibility. Maybe the harshness of Trump’s crackdown is forcing an overdue conversation. Maybe hostile architecture shows us what happens when we try to design our way out of guilt instead of solving problems.

At the end of the day, the choice cannot simply be between spikes on benches or jail cells. The real solution must lie in something more ambitious: housing that is affordable, healthcare that is accessible, and a society that does not see homelessness as inevitable. Until then, we are left with the uneasy task of asking ourselves: if neither hostile architecture nor forced facilities are acceptable, then what will we do instead?

Because in the end, for every person sleeping on the streets, the question of compassion isn’t abstract. It’s immediate. And it’s not just the government’s burden. It’s ours too.