History and Contributions of Muslims in Canada Reminds Us of Our Values

- Maryam Ahmed

- Breaking News

- Canada

- July 19, 2022

Muslims continue to enrich Canadian Society even in the face of bigotry

Canada is well known for its diverse and multicultural society. The government officially adopted multiculturalism in Canada during the 1970s and 1980s. As a result of its public attention to immigration’s social importance, the Canadian federal government is described as the catalyst of multiculturalism.

Canadians have used the term “multiculturalism” in different ways: descriptively (as a sociological fact), prescriptively (as ideology) or politically (as policy). In the first sense, “multiculturalism” describes the many different religious traditions and cultural influences that in their unity and coexistence result in a unique Canadian cultural mosaic.

The nation comprises people from many racial, religious, and cultural backgrounds and is open to cultural pluralism. A considerable number of people who contribute to this rich multicultural society are Muslims.

The presence of Muslims in Canada dates back to 1854, with the first recorded birth of a Muslim to Scottish parents James and Agnes Love. From then on, history shows a small, diverse, and widely dispersed community making noticeable impacts from right around the turn of the century and beyond. Neither modest size nor vast distances seemed to deter Canadian Muslims from contributing to bettering their communities.

The first Muslim contribution to the fields of literature and history belongs to Mahommah Baquaqua in the mid-1850s. Baquaqua was of West African origin and was enslaved in Brazil before attaining freedom in the United States and making his way up to Canada through the famous Underground Railroad. In 1854, while living in Ontario, he orally narrated his story, a project that culminated in an autobiography that remains the only known slave narrative from Brazil. Such slave narratives eventually helped to abolish slavery in the United States and elsewhere.

Many of the earliest Muslim immigrants to Canada were successful entrepreneurs. For instance, Bedouin Ferran, also known as Peter Baker, arrived in 1910 and slowly made his way to the Northwest Territories, where he worked as a fur trader and would eventually contribute to the fields of literature and politics. In 1964, Ferran became one of the first Muslims to be elected to public office in Canada, representing a primarily Indigenous riding in the Northwest Territories.

During the Great Depression, Hilwi Hamdon led the initiative to establish Canada’s first mosque, contributing to Canada’s diverse heritage. She approached Edmonton Mayor John Fry with the idea and brought different communities together to build the Al-Rashid Mosque – which is now a heritage site. The first Qur’an teacher to teach at the mosque, Ameen Ganam, would later become an award-winning musician and is still known today as “Canada’s King of the Fiddle.”

Husain Rahim, an Indian Muslim, was an early interfaith leader and activist based in Vancouver. He ran his newspaper, The Hindustanee, for the budding Indo-Canadian community, in 1914, making him Canada’s first known Muslim journalist. He brought attention to the discriminatory laws against South Asians. He was on trial once for migrating to Canada and the second time for allegedly voting in an election. During the infamous Komagata Maru incident, Rahim strove to have the migrants from South Asia allowed into Canada.

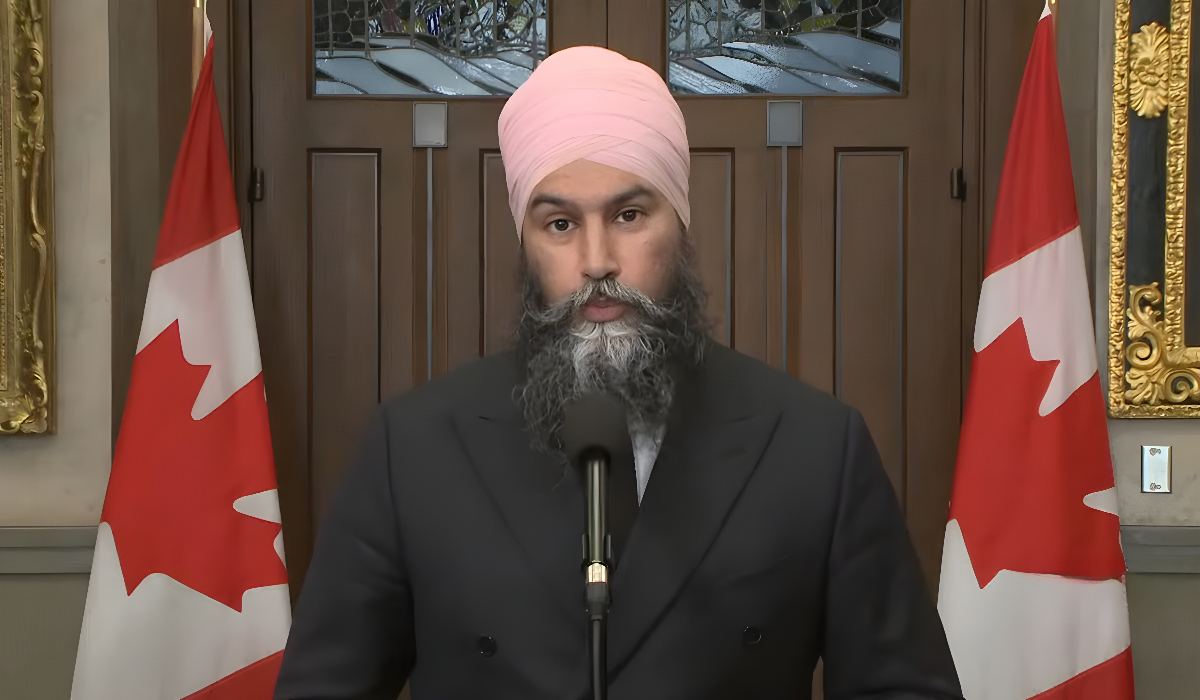

Despite the groundbreaking contributions Muslims have made to Canadian society, they haven’t gone without their share of prejudice and injustice. For Canadian Muslims, the opportunity to commemorate and celebrate their history since pre-Confederation comes at a critical juncture. Those who hold bigoted and racist views have become more vocal – emboldened by populist politics that can fuel fear of the “other” and engender the disillusioned to turn against minority communities. If ever there was a time to fully acknowledge and appreciate various communities’ contributions to Canada’s prosperity and richness, it is now.

To this swath of citizens, Muslims aren’t proof of all Canadians’ abilities to blend into a single cohesive society; they’re evidence of some Canadians’ reluctance or inability to “blend in” at the expense of a cohesive society. That is, after all, the expressed rationale for Quebec’s Bill 21, a ban on religious symbols whose main target, everyone agrees, is Muslim women and girls. Less subtly, it’s the rationale for one of the People’s Party of Canada’s core platforms promises to repeal the Multiculturalism Act and defund multiculturalism initiatives, thereby ending a 50-year experiment to divide Canadians into “a collection of ethnic and religious tribes living side by side.”

Even as the winds of Islamophobia blew in from the Palestinian-Israeli conflicts, Iranian Islamic Revolution, Gulf War, and, of course, the September 11 attacks, Muslim Canadians have been able to safely and peacefully claim their religious holidays, infrastructure, and symbols in public. And, because many Muslims practice and often wear their religion as a matter of daily life, they have become symbols, too.