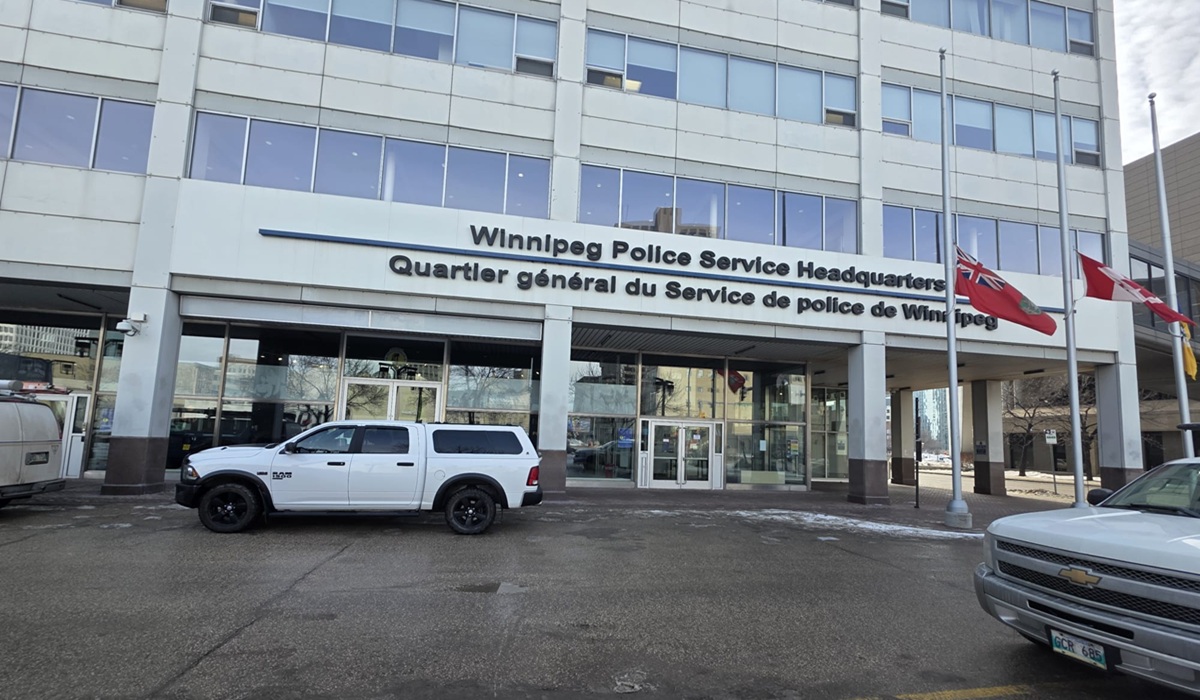

Firefighters Reach Year 2040 Call Volumes — Council Votes Unanimously to Amend the Budget

- Don Woodstock

- Breaking News

- December 17, 2025

For years, Winnipeg’s firefighters and first responders have been saying the same thing: the system is being pushed beyond what it was ever designed to handle. Call volumes have been rising faster than staffing, faster than budgets, faster than recovery. Overtime has become routine. Burnout has become structural. Mental health injuries have followed.

And for years, those warnings were minimized, delayed, or quietly set aside.

To understand the significance of what happened at City Hall, it is essential to be clear about one fact that finally cut through the noise. The number of emergency calls Winnipeg firefighters are responding to today is the level planners once projected would not be reached until the year 2040. In plain terms, firefighters are already working under conditions expected to exist fifteen years from now, without the staffing levels that were supposed to accompany that future. That gap has been carried on the backs of firefighters through endless overtime and cumulative trauma.

This reality did not arrive overnight, and it did not go unnoticed by the people living it.

Today, that reality was laid bare in council chambers by firefighter-paramedic Adrienne Hobbs, stationed at downtown Station One, one of the busiest fire stations in North America. Hobbs did not speak in abstractions. She spoke about what under-resourcing looks like in real time, on real calls, and on what are supposed to be days off.

“I love my job. I always have,” she told council. “But I am here today because this budget does not reflect the reality of the work we do, or the cost of continuing to under-resource it.”

She described firefighters going home on their days off knowing rest may not come. Knowing the phone could ring at any moment with another call for overtime because if they do not answer, a truck may be taken out of service and response times stretch longer for the public.

She described what those calls entail. The cardiac arrest of a three-year-old girl drowned in a bathtub, the feel of her cool skin, the bruises that told a deeper story. A sixteen-year-old girl whose legs were crushed under a bus while trying to get home, her life permanently changed. A fourteen-year-old girl thrown from a vehicle travelling nearly 200 kilometres an hour by a drunk driver, and the unrelenting guttural scream of her mother, a sound Hobbs said she will carry for the rest of her life.

She spoke as well about the work the public rarely sees: returning to scenes after police leave to wash away blood, tissue, and bone fragments so the city does not have to confront what remains.

“These are not rare calls,” Hobbs said. “They are routine. And these examples happened on overtime. Extra shifts. Extra trauma.”

What made her testimony so powerful was not emotion alone, but clarity. It connected years of research, actuarial projections, and operational data to lived experience. It gave council something it could no longer abstract away.

That clarity did not emerge by accident.

For years, United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg President Nick Kasper has been advocating on behalf of firefighters — not simply as a labour leader, but as a steward of public safety. His efforts were unrelenting, not because of politics, but because of consequence. Protecting the mental health of firefighters is inseparable from protecting the safety of the city they serve. A burned-out firefighter is not just a personal tragedy; it is a public risk.

Kasper understood that data alone was not enough. He understood that behind every chart was a human being expected to wake up, put on a uniform, and carry trauma home so the city could function. It was with that foresight that Hobbs was asked to speak — to give council a first-hand account of what the system was asking of firefighters and what it was costing them. That testimony, grounded in lived experience, may well have been the catalyst that moved the decision from debate to action.

Even so, the distance between City Hall and the fire service was laid bare before a single word was spoken.

Before entering the gallery, firefighters were told they could not wear shirts identifying themselves as firefighters. They were instructed to turn them around or remove them entirely. Not slogans. Not protest messaging. Simply identification.

In a space where citizens regularly attend wearing jerseys, union apparel, organizational insignia, and cause-based clothing without issue, the instruction landed as something else entirely. To many in attendance, it felt like a deliberate dressing down — a reminder that firefighters could speak, but should not visibly exist.

That moment mattered because it echoed years of how firefighters felt treated: required to justify themselves, asked to prove what they already live, made to feel their warnings were an inconvenience rather than expertise.

Inside the chamber, however, unity was unmistakable. Firefighters from every level of the service were present. Fire brass stood alongside line firefighters. Kasper was there. Captain Laura Klassen Dawson was there. The message was not fragmented. It was collective, disciplined, and resolute.

Following Hobbs’ testimony and sustained advocacy that could no longer be ignored, Winnipeg City Council voted unanimously to amend the budget and provide additional resources to the fire service. It was a rare outcome and a meaningful one. It signaled that City Hall, finally, was prepared to align its decisions with the reality on the ground.

Relief is now coming. Firefighters may begin to experience real days off. Recovery may become possible rather than theoretical. The constant cycle of forced overtime and compartmentalized trauma may finally start to ease.

At the same time, the path to this moment invites reflection.

Budgets are not accidents. They are choices. If the city had the power to act now, it had the power to act earlier. Firefighters should never have had to reach this point, nor should it have required an unprecedented amendment for essential public safety needs to be addressed.

It would also be naïve not to acknowledge context. Next year is an election year. Public safety resonates deeply with voters, and elected officials are accountable to the people they serve. That does not diminish the importance of the decision made — but it does raise a fair question. Had this not been an election cycle, would this amendment have passed so decisively?

That question is not an accusation. It is part of honest civic accountability.

What matters now is follow-through. The details will define whether this unanimous vote translates into real change: how many firefighters are hired, how quickly they are onboarded, how staffing models adjust, and whether administrative delays quietly slow what was so clearly supported in principle.

Winnipeg has shown that it can act decisively when it chooses to. The coming months will reveal whether that resolve carries through implementation.

For now, one thing is clear. Winnipeg’s firefighters were forced to operate at year-2040 call volumes far earlier than anyone planned. They warned of the consequences. They were ignored for too long. This time, they were finally heard.

And for the people who run toward danger so the rest of the city does not have to, that acknowledgment — paired with action — matters.