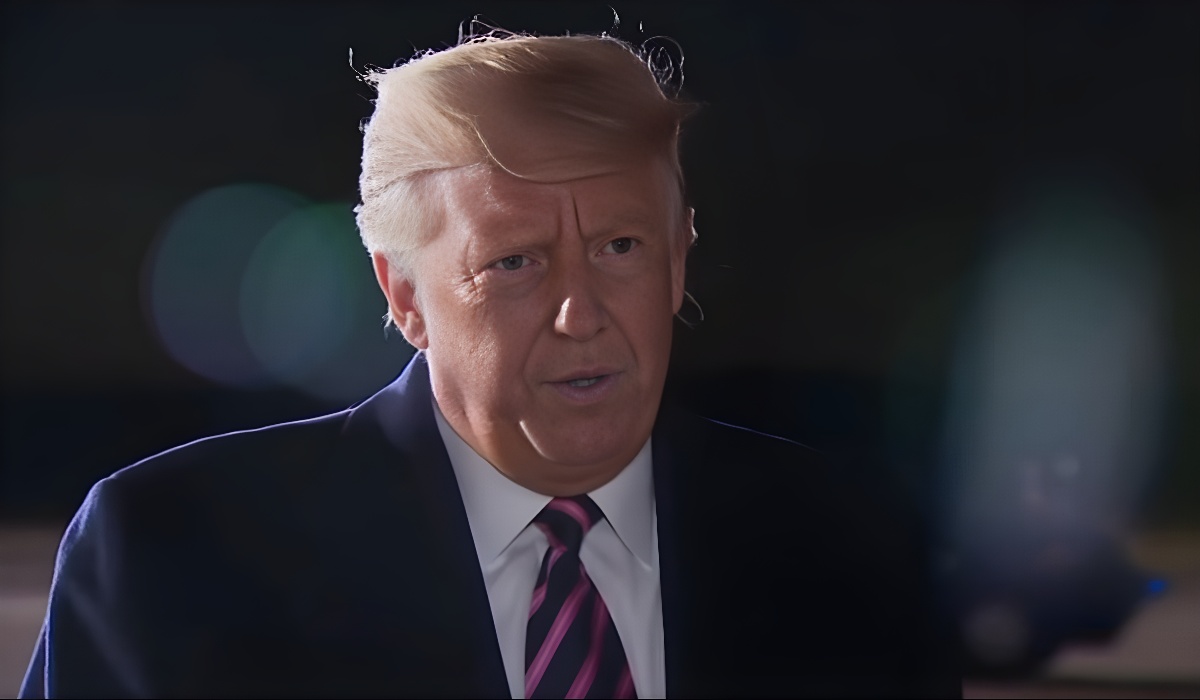

El Salvador Abolishes Presidential Term Limits: Power Grab or Path to Stability?

- Ingrid Jones

- Breaking News

- Latin

- August 1, 2025

Image Credit: Nayib Bukele, Social Media

In a historic and highly polarizing move, El Salvador has officially abolished presidential term limits, marking a dramatic shift in the country’s democratic architecture. The decision, backed by President Nayib Bukele’s administration and approved by a legislative supermajority, has set off a wave of debate both within and beyond El Salvador’s borders. Supporters hail it as a bold step toward national continuity and stability. Critics condemn it as a calculated power grab with dangerous precedents, reminiscent of Latin America’s darker chapters.

To understand the significance of this development, it’s crucial to trace the roots of El Salvador’s political evolution.

El Salvador’s modern democracy was born from conflict. After a brutal 12-year civil war that ended in 1992 with the signing of the Chapultepec Peace Accords, the country began building its post-war democratic institutions. Central to those institutions was the belief in checks and balances—especially term limits. The Salvadoran Constitution prohibited immediate presidential re-election as a safeguard against dictatorship, a legacy rooted in decades of authoritarian rule under military juntas and strongmen like General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez.

The constitutional ban on re-election was more than just a rule—it was a reflection of collective trauma. El Salvador, like much of Latin America, bore deep scars from leaders who clung to power, often suppressing opposition with brutal force. The one-term presidency was designed to prevent the rise of another autocrat.

But the democratic experiment in El Salvador has always been fragile, vulnerable to corruption, political dysfunction, and gang violence. Trust in institutions remained low. And it’s in this context that the presidency of Nayib Bukele emerged.

President Bukele’s rise to power was meteoric. A former mayor of San Salvador, he branded himself as the outsider—the anti-politician, the millennial reformer, the man who would break the traditional two-party stranglehold on power. His party, Nuevas Ideas, quickly gained massive popularity, leveraging social media savvy and anti-establishment rhetoric.

But Bukele’s appeal wasn’t just style. It was substance—particularly in the form of unprecedented public safety. Under his controversial anti-gang crackdown, the country has witnessed a drastic drop in homicides. El Salvador, once among the most dangerous countries on Earth, now boasts one of the lowest crime rates in the region. Streets once dominated by MS-13 and Barrio 18 have been reclaimed by ordinary citizens. For the first time in generations, Salvadorans can walk through neighborhoods at night without fear.

This newfound security has earned Bukele the adoration of millions. He’s often portrayed in glowing terms on social media as a leader who “gets things done,” even if that means sidelining traditional checks and balances.

The push to abolish presidential term limits began in earnest in 2021, when the country’s top court—stacked with Bukele loyalists following a legislative shakeup—ruled that re-election was constitutionally permissible. That decision opened the door for Bukele to run again in 2024, and now, the law has been formally amended to remove term limits altogether.

Proponents argue this change reflects the will of the people. Bukele maintains sky-high approval ratings—often over 80%—and his administration insists that continuity is essential for completing national reforms. They say rigid term limits arbitrarily cut short effective leadership and deprive voters of the right to choose the leader they want.

“We are building a new El Salvador,” one Nuevas Ideas legislator said. “Why would we stop that progress midstream?”

The government frames the reform as a matter of sovereignty, stability, and modernization—a challenge to Western-imposed democratic norms that no longer fit El Salvador’s current reality.

But critics warn that this move erodes democracy in irreversible ways. By eliminating term limits, El Salvador is stripping away one of the few institutional brakes on executive power. Opponents fear this is just the latest step in a broader project to consolidate authority—one that includes attacks on press freedom, the militarization of politics, and the marginalization of opposition voices.

Regional observers point to Venezuela and Nicaragua, where similar moves to remove presidential limits preceded democratic backsliding and economic collapse. Human rights organizations have issued urgent alerts about the shrinking space for dissent.

And yet, domestically, the opposition’s warnings often fall on deaf ears. Many Salvadorans see the transformation of their country as tangible and deeply personal. A mother who can now let her child walk to school without fear of being kidnapped. A shopkeeper whose business no longer pays extortion fees to gangs. These everyday changes speak louder than democratic theory.

El Salvador’s abolition of term limits forces a deeper global question: what happens when democracy is used to dismantle its own safeguards? If a leader is popular, if the people demand continuity, should constitutions bend?

It is a question as old as democracy itself. The ancient Athenians feared demagogues. The American Founders feared the tyranny of the majority. Latin America has long feared the strongman. Yet in El Salvador, the population appears to fear a return to the past more than the overreach of a single man.

President Bukele argues that he represents a new paradigm—one where stability, safety, and results matter more than abstract ideals. His supporters echo this sentiment, claiming that El Salvador is no longer a “banana republic,” but a rising nation charting its own course.

Whether history will vindicate this decision or condemn it remains to be seen. What’s clear is that the abolition of term limits marks a turning point—not just in Salvadoran politics, but in the very meaning of democracy in the 21st century. Is democracy only about process and institutions, or can it also be about security, order, and public satisfaction?

Time, as always, will deliver the final verdict.