A Continent of 1.5 Billion Is Rewriting the Language of Justice

- TDS News

- Breaking News

- Africa

- February 20, 2026

By: Donovan Martin Sr, Editor in Chief

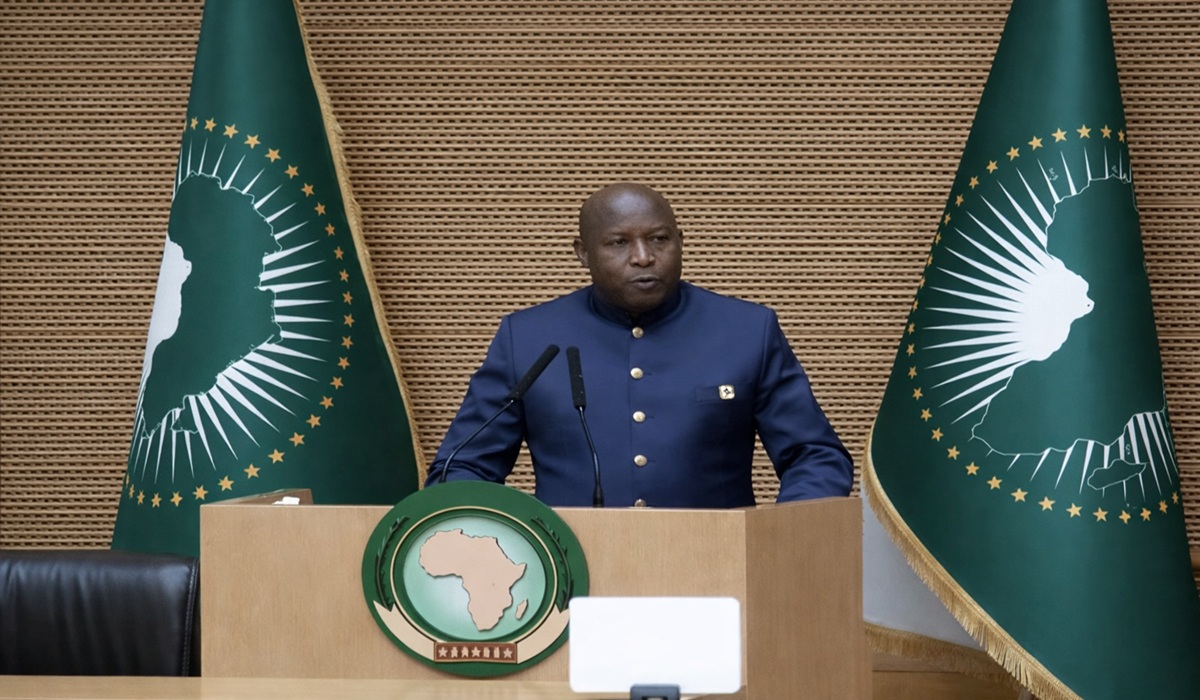

In Addis Ababa this February, the African Union did something that may prove more consequential than any single summit communiqué. It reframed slavery, colonialism, and the forced deportation of African peoples not as tragic chapters of a distant past, but as crimes whose consequences remain alive in the present. For a continent of roughly 1.5 billion people, this was not rhetorical theatre. It was an assertion that history cannot remain a footnote in global law while its aftershocks continue to shape borders, economies, and power.

For decades, former colonial powers such as the United Kingdom and France have expressed regret for aspects of empire. Regret, however, is carefully engineered language. It acknowledges pain without admitting liability. It gestures toward reconciliation while sidestepping restitution. Formal apologies have been rare and narrowly framed, and comprehensive reparations tied to a legal admission of wrongdoing have never materialized. That reluctance is not accidental. Recognition of colonialism and slavery as crimes against humanity would not simply alter textbooks; it would expose governments to structured claims grounded in international law.

The African Union’s position signals impatience with symbolic remorse. If embedded into binding continental instruments and national legislation, the declaration becomes a platform for coordinated diplomacy at the United Nations. The objective would be clear: to elevate slavery and colonialism into the formal category of crimes against humanity under global legal frameworks. Such recognition would not automatically generate compensation, yet it would establish a legal architecture upon which claims for restitution could be constructed.

The obstacle is structural. The United Nations Security Council, the body that carries the greatest authority in matters of international peace and security, is composed of five permanent members with veto power and ten rotating members. The permanent members are the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and China. No African nation holds a permanent seat. Africa rotates through three non-permanent seats shared among 54 states, despite being the subject of a substantial portion of the Council’s deliberations. The African Union’s Ezulwini Consensus demands at least two permanent seats with veto power and five non-permanent seats for the continent, a reform discussed for years yet never implemented. Altering that structure requires agreement from those who already benefit from it, and entrenched power rarely concedes itself willingly.

Even if a majority of UN member states supported recognition of colonialism as a crime against humanity, the path to enforceable change would be steep. Security Council vetoes can block substantive action. Amendments to the UN Charter demand supermajorities and ratification by existing permanent members. Legal debates over retroactivity would surface immediately, with opponents arguing that modern definitions of crimes against humanity cannot be applied to conduct predating those frameworks. Domestic political pressures within Europe would complicate matters further, as electorates confronting economic uncertainty question large-scale financial obligations tied to historical events.

Yet improbability does not negate significance. The African Union’s declaration is not solely a legal maneuver; it is a strategic repositioning of narrative authority. It reframes colonial extraction as organized exploitation that reshaped global capital flows, redirected raw materials outward, imposed artificial borders, and entrenched economic dependency. It asserts that forced deportation, whether across oceans during the transatlantic slave trade or through internal displacement under colonial administration, fractured societies in ways that still reverberate through debt burdens, trade imbalances, and fragile infrastructure.

Reparations, if pursued seriously, would require more than emotional appeal. They would demand methodology. Economic modeling could examine centuries of labor exploitation, resource transfer, and capital accumulation. Compensation might take the form of direct payments, structured development funds, debt cancellation, sovereign wealth contributions, or climate finance offsets tied to the industrial wealth built during empire. Without defined mechanisms, critics dismiss reparations as limitless liability rather than structured redress. With defined mechanisms, the conversation shifts from abstraction to policy.

Cultural restitution remains one of the most tangible dimensions of this debate. Tens of thousands of African artifacts reside in European museums and private collections. Sculptures, royal regalia, sacred objects, manuscripts, and ceremonial works removed during military campaigns and administrative seizures continue to sit behind glass cases in London, Paris, and beyond.

Some institutions have begun returning select pieces, often described as long-term loans rather than full restitution. That distinction carries weight. A loan implies retained ownership. Restitution acknowledges dispossession. For many African leaders and scholars, the continued presence of these artifacts abroad symbolizes an unfinished reckoning. If colonial extraction is framed as criminal, then cultural property becomes more than shared heritage; it becomes evidence of unlawful removal.

The reparations debate also intersects with climate justice. Industrial expansion during empire accelerated carbon emissions whose consequences now disproportionately affect African states through drought, flooding, and food insecurity. Framing reparations alongside loss-and-damage climate finance strengthens the argument that historical extraction and contemporary vulnerability are linked.

None of this absolves post-independence governance failures or internal challenges within African states. Colonialism does not erase contemporary responsibility. Yet acknowledging present shortcomings does not negate the structural starting points imposed by centuries of external control. Both realities can coexist without canceling one another.

Geopolitics complicates the landscape further. Emerging powers may support reform rhetorically when it weakens Western moral authority, yet remain cautious about precedents that could generate liability in other contexts. Diaspora communities across the Caribbean, North America, and Latin America add additional pressure, broadening the issue beyond state-to-state diplomacy into a transnational movement for historical accountability.

The deeper paradox is stark. A continent of 1.5 billion people, immense natural resources, and 54 sovereign states remains without a permanent veto voice in the body that shapes global security decisions. The same continent is frequently the subject of those decisions. That imbalance reflects a post-World War II power structure frozen in time while demographics and economic realities have shifted dramatically.

Whether the United Nations ultimately recognizes colonialism and slavery as crimes against humanity in the near term remains uncertain and, realistically, unlikely given existing veto structures. However, the shift in language itself alters diplomacy. It strengthens Africa’s negotiating position on debt, trade, cultural restitution, and institutional reform. It transforms regret from sufficient response into insufficient gesture.

History has often been narrated by those who possessed the authority to define legality. The African Union’s declaration challenges that authorship. It insists that justice cannot remain symbolic when material consequences endure. Even if structural reform at the UN proceeds slowly, the pressure will not dissipate. It will mature, recalibrate, and persist.

A continent is asking not merely for apology, but for alignment between moral acknowledgment and legal consequence. The answer to that demand will determine whether global institutions evolve with demographic reality or remain anchored to the architecture of an earlier age.