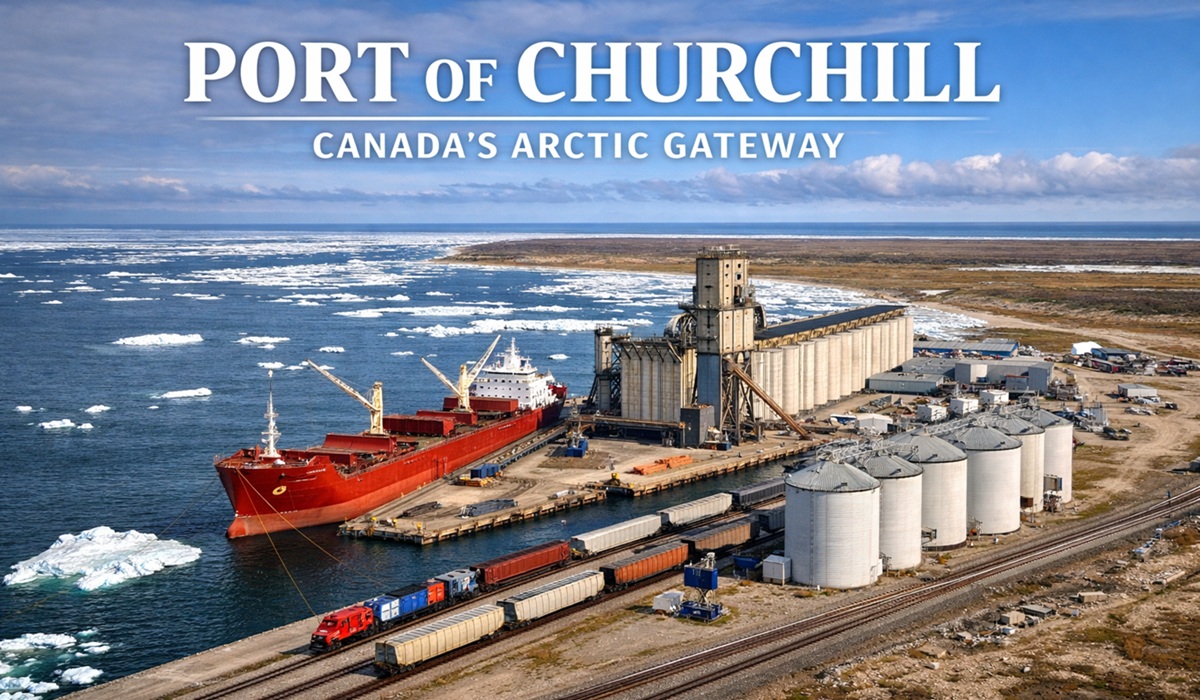

How the Port of Churchill Shields Canada from Tariffs, Sanctions, and Trade Risk

- TDS News

- Canada

- January 18, 2026

By: Donovan Martin Sr, Editor in Chief

For most of its existence, the Port of Churchill has been treated as a regional curiosity rather than a national asset. That framing has always been wrong. Designed not as a commercial afterthought but as a strategic instrument of sovereignty, food security, and economic independence, the port’s relevance has only grown with time. When viewed through the combined lenses of history, geography, trade economics, and modern geopolitical risk, a strong case can be made that once fully operating at scale, Churchill may become the most strategically important port in Canada.

Conceived in the early twentieth century with a clear purpose: to serve the people of the Prairies and the nation as a whole by providing a direct northern outlet to global markets. Completed in 1931 and linked to southern Manitoba by the Hudson Bay Railway, it was envisioned as a shorter, cheaper route for exporting grain to Europe. At a time when rail distances and shipping days directly determined competitiveness, this was a concrete advantage. Grain loaded in northern Manitoba could reach European markets with fewer unnecessary kilometres baked into the supply chain than cargo routed through the Great Lakes or the Pacific. For decades, the port fulfilled that role, anchoring a northern export corridor that was meant to function as infrastructure first and commerce second.

That trajectory was interrupted not by geography or economics, but by political neglect. In the 1990s, the federal government divested itself of the port and railway, ultimately selling them for one dollar to OmniTRAX. The logic was privatization. The consequence was that a strategic corridor was left vulnerable to private risk tolerance. When severe flooding in 2017 washed out large sections of the rail line, the company walked away, cutting off the only land access to Churchill. Supplies had to be airlifted. Residents and businesses were stranded. A national asset was effectively left to fail because it no longer fit a private balance sheet.

That moment exposed a basic truth Canada too often forgets. Ports and railways are not only commercial assets. They are resilience systems. In 2018, ownership and operations shifted to the Arctic Gateway Group, a Canadian-led partnership that includes significant First Nations and northern community participation. The corridor was restored and the port reopened. The deeper issue, though, was never just reopening. It was whether Canada would finally treat the route as the strategic instrument it was built to be.

Geography is the reason this matters. Churchill sits on the western shore of Hudson Bay, a direct northern doorway to Atlantic-facing trade routes. For producers in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, that geography offers a straight north line instead of a long south detour. It is difficult to overstate how much distance gets wasted in the current default model. Prairie commodities are routinely shipped thousands of kilometres to Vancouver, then loaded and sailed across the Pacific or routed back toward markets that are actually east of Canada. Other volumes move through inland routes that face congestion and chokepoints. By contrast, a northern outlet through Hudson Bay can shave meaningful time off voyages to European buyers and other Atlantic destinations, sometimes by days and in certain routes by weeks, while removing thousands of kilometres of rail and marine travel that serve no Canadian interest except inertia.

For decades, Canada also normalized routing strategic exports through the United States. Grain, potash, and other bulk goods have travelled south by rail into American ports and logistics systems before being loaded for overseas destinations. It worked while the political relationship was predictable. It becomes a liability when the relationship is not. Using American infrastructure is not just a routing choice. It is an exposure choice. It means American rail, American port fees, American carriers, American freight forwarders, and American regulatory and political leverage sit inside the middle of Canadian supply chains. In a calm world, that looks efficient. In a hostile world, it looks like a mistake.

That is why potash belongs at the centre of any serious discussion about the strategic value of Churchill. Canada is the world’s largest potash producer, responsible for about 32 percent of global production in 2023, and it holds the world’s largest known reserves, with roughly 1.1 billion tonnes. Those reserves sit largely beneath the Prairie provinces, meaning the resource and the rail geography naturally point toward a northern export corridor if Canada chooses to fully activate it.

The United States, meanwhile, is structurally dependent on imported potash. It imports more than 95 percent of the potash it uses. Of those imports, roughly four-fifths come from Canada, making Canada by far the dominant supplier to American farmers. Without fertilizer, modern agriculture breaks. Yields fall. Food prices rise. Entire farm economies destabilize. That is not theory. It is arithmetic.

In 2025, President Donald Trump threatened tariffs of 25 percent or higher on Canadian imports, and potash was drawn into that tariff threat environment. The threat was politically loud and economically confused, because a tariff on Canadian potash is not a cost imposed on Canada first. It is a cost imposed on American farmers first, and then on American consumers through food prices. As the pressure mounted from farm-state realities and industry pushback, the policy was walked back and potash duties were reduced rather than escalated, reflecting the inevitable correction that happens when economic basics collide with political theatre. Someone in that administration had to explain, in plain terms, that you cannot punish the supplier of a critical input without punishing your own production base.

That episode is precisely the point. Canada cannot build strategic trade policy around the assumption that the next threat will be rational, informed, or consistent. When a neighbour can credibly threaten tariffs, carve-outs, exemptions, and reversals within the same year, dependency is not just risky, it is negligent. It is in that environment that a northern Canadian port stops being a “regional project” and starts looking like a national shield.

This is where the strategic logic becomes unavoidable. If Canada can move Prairie commodities north to Churchill and out through Hudson Bay, it is not simply saving distance. It is reducing exposure. It is cutting American intermediaries out of rail, shipping, logistics, and port handling. It is keeping margin, jobs, and industrial capacity inside Canada. It is also removing the ability of U.S. political actors to turn Canadian supply chains into bargaining chips by controlling the infrastructure those chains rely on.

That strategic shift is not hypothetical. It is already being framed in government as infrastructure of national interest. Since 2018, the federal government has invested more than $320 million to support the Arctic Gateway Group in acquiring, restoring, maintaining, and developing the Hudson Bay Railway and the Port of Churchill. In March 2025, Ottawa announced a five-year package of $175 million to maintain rail service and begin pre-development work tied to the port’s next phase. Manitoba’s investment has also been positioned as strategic corridor development, with provincial funding bringing total provincial participation in the project to $87.5 million and combined federal-provincial investment over five years described as $262.5 million.

Those numbers matter because they signal intent. Governments do not put long-horizon money into a corridor like this unless they have concluded it serves more than local needs. The federal framing is explicit about corridor development, trade diversification, and northern resilience, while the ownership model directly advances Indigenous economic participation in a way Canada historically talks about more than it executes. First Nations ownership is not a footnote here. It is part of the point. A sovereign trade corridor that excludes Indigenous equity would be repeating the old model under a new banner.

There is also a wider national-security and sovereignty context that rarely gets said plainly. Northern infrastructure is sovereignty. It anchors year-round capability, resupply potential, and economic presence in a region that is only becoming more contested and more commercially relevant. Even without dramatizing Arctic geopolitics, it is a simple fact that a country’s infrastructure footprint shapes its strategic reality. A functioning northern port integrated with a continental rail network gives Canada optionality it does not otherwise have.

So why has Canada not seen this corridor fully activated before. Part of the answer is cultural. Canada has often managed nation-building assets as though they were discretionary rather than foundational, preferring to route value through existing systems even when those systems sit outside Canadian control. Part of the answer is political. Long-term trade infrastructure rarely fits short electoral cycles. And part of the answer is that Canada has not always been forced to confront how quickly a friendly neighbour can turn transactional.

That is the uncomfortable upside of the recent tariff era. It has forced Canada to think like a country that must stand on its own infrastructure. If the United States wants to say it does not need Canada, Canada should treat that as useful information rather than an insult. The correct response is not resentment. It is capacity. Building out Churchill to its full potential is not about being anti-American. It is about being pro-Canadian, in the most literal sense of controlling the routes that move Canadian wealth to global markets.

Once fully operational at scale, the Port of Churchill is not just an export point. It is a national pressure valve. It can shorten routes to global buyers, reduce dependency on foreign infrastructure, keep logistics value in Canada, and offer Prairie producers an option that is strategically insulated from tariff politics. History shows what happens when it is treated as optional. The current trade environment shows what happens when Canada relies too heavily on systems it does not control. The future, if Canada is serious about sovereignty in economics as well as borders, points north.