What Factors Led City Council to Target the Granite Curling Club Parking Lot for Housing?

- Don Woodstock

- Canada

- December 30, 2025

There is a way to build housing in Winnipeg that feels like common sense. There is also a way to build housing that feels like a decision was made first and the justification written later. The Granite Curling Club parking lot is starting to feel like the second kind.

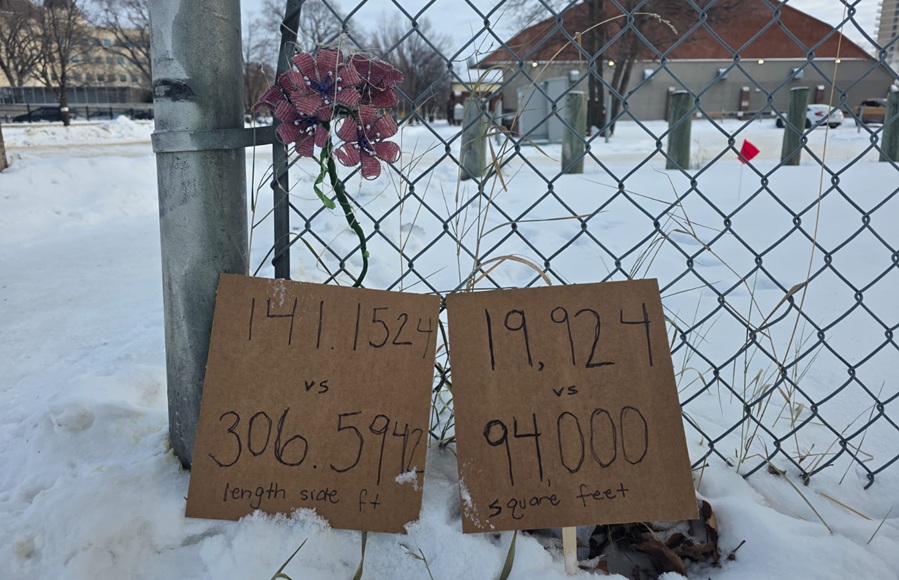

The City of Winnipeg is pursuing a development plan that relies on taking a portion of the Granite Curling Club’s parking lot at 22 Granite Way. It has been framed as a key Housing Accelerator site and presented as progress. But when you look closely, the questions begin to crowd out the assurances. Why now? Why this exact spot? Why a section of a parking lot attached to one of the most significant curling clubs in Western Canada? And in a city full of vacant buildings, surface parking lots, and underused land, why does the solution have to begin here?

Winnipeg accepted federal Housing Accelerator funding. That funding matters. It creates pressure to show movement and results. But it was never meant to excuse poor site selection. The objective was to move housing forward faster, not to move it forward without logic. A rushed decision that leads to years of conflict, legal challenges, and neighbourhood disruption is not acceleration. It is a detour disguised as progress.

If the City wants the public to accept this choice, it must answer the obvious question: why did this specific piece of land become the solution? Winnipeg is not short on alternatives. Downtown has vacant and underused buildings that could be converted into housing with far less disruption and without triggering a parking crisis. The City also owns surface parking lots that sit empty and unproductive year after year. Those sites are already cleared, already serviced, and already positioned to support density. If the goal is housing near services and transit, many of those locations appear to fit better, with fewer consequences.

Targeting the Granite parking lot was not inevitable. It was a choice. And choices demand explanation.

The City’s own language does not provide one. It describes the west parking lot at 22 Granite Way as a key site under the Housing Accelerator program. But calling something key does not explain why it was chosen. What makes it key compared to other City-owned properties? What alternatives were evaluated? Who performed the comparison? What criteria were used? If those answers exist, they have not been shared. If they do not exist, that absence is telling.

The project is also described as delivering affordable homes. The phrase sounds reassuring, but it is vague. Affordable can mean different things depending on definition, duration, and enforcement. This is river-adjacent land overlooking the Assiniboine. That is prime real estate. It is difficult to believe that brand-new housing in this location will meaningfully serve those most in need without unusually strong safeguards. Residents are entitled to ask: affordable for whom, for how long, and under what protections?

Which brings us to the question that hangs over everything. Who benefits?

Someone always does. A developer benefits. A land-value narrative benefits. A political storyline benefits. A housing metric benefits. Something benefits. The public deserves to know which interests gain the most from choosing this exact site, because this is not a neutral planning decision. It is a high-value land decision.

The most immediate consequence is also the most obvious: parking.

The City’s own statements treat parking as manageable. They suggest it will be worked out. They say discussions will continue. Translated into plain language, the message is simple. The project proceeds first. Parking gets negotiated later. That is not a plan. It is a postponement.

This area already struggles with parking. Residents already compete for space. Visitors already circle blocks. Winter already compresses what little curb space exists. If the Granite parking lot loses capacity, those vehicles do not disappear. They migrate. They spill onto public streets. That means more congestion, more enforcement, more tickets, more frustration, and more conflict — not because residents are unreasonable, but because space is finite.

So far, there has been no clear explanation of how that spillover will be prevented. There has been no clarity on how many stalls will be lost. There has been no detailed explanation of what off-site parking means in real terms — in walking distance, winter conditions, or for people hauling equipment. Enforcement strategies have not been outlined, nor has it been explained who would pay for them. Residents are being asked to trust that it will be resolved later.

If ground-level replacement cannot solve the problem, the conversation inevitably shifts below grade. There has been no commitment to structured underground parking, and that reality comes with consequences. Building below grade near the Assiniboine is not routine. Excavation in that environment can require extensive shoring, reinforced retaining walls, and continuous groundwater management. Engineers must account for hydrostatic pressure, soil behaviour, and seasonal water fluctuations. Digging near a riverbank introduces risk and complexity that drives costs sharply upward. Even stabilizing the site can become a major engineering undertaking before a single stall is created.

If no below-grade solution is pursued, the missing stalls migrate into the neighbourhood. If one is pursued, the financial implications can be enormous. Either way, the cost does not disappear. It is simply transferred.

And if subsurface construction proves impractical or financially prohibitive, another question becomes unavoidable. Where does replacement parking come from? There is no surplus land next door waiting to be absorbed. Any attempt to expropriate neighbouring property would be extraordinarily costly. Large institutional landholders are not easily displaced. The legal, financial, and political consequences would dwarf the assurances currently being offered.

Which circles back to the same question. Why this site in the first place?

That question becomes harder to ignore given what sits immediately next door. A larger, publicly controlled park occupies the former Canada Post building site. Nobody casually supports removing green space. But this location has not become a vibrant family destination. By many accounts, it is underused by residents and frequently associated with disorder and drug activity. That is not an accusation. It is a reality neighbours already experience.

If the stated goal is housing for families near services, why was this adjacent publicly managed land not the first option? It is larger. It is already maintained with public resources. It appears to be roughly twice the size of the portion of parking now being targeted. It would avoid destabilizing existing parking patterns. It would reduce spillover. It would avoid forcing a long-standing community institution into legal conflict. It would also solve two problems at once by adding housing and replacing a space currently associated with disorder with something supervised and purposeful.

So the question becomes unavoidable. Why not this land? Was it evaluated? Was it compared? Was it dismissed? Was there a formal analysis? If so, where is it? If not, why not?

If decision-makers believe they can justify rezoning a portion of an active curling club’s parking lot, they should be able to justify evaluating a larger, publicly controlled site next door. If that land has a federal history, that does not end the conversation. Governments work with governments. Public purpose evolves.

Instead, the chosen path increases friction. It triggers litigation. It forces a community institution to spend money on lawyers. It creates uncertainty. It invites suspicion. It consumes time that could have been spent building housing elsewhere, with far less conflict.

And this is where non-disclosure agreements enter the picture — and where the public has every right to grow uneasy. For years, Winnipeggers have heard about NDAs being required in major land and development discussions, agreements signed not only by private developers but by senior administrators, political staff, and sometimes elected officials themselves. NDAs are often justified as routine, yet their repeated use in public land matters raises a basic question. Why is secrecy required at all when the land belongs to the public and the consequences fall on residents?

If NDAs were used here, what information was considered too sensitive to share? Was it financial modeling? Land valuation? Comparative site analysis? Risk exposure? Legal strategy? Or the sequence of decisions that led to this site being selected over others?

NDAs are not inherently illegal. But when they are embedded in public decision-making, they restrict transparency by design. They limit what can be said, by whom, and when. They ensure residents often learn only what they are permitted to learn, long after meaningful input is possible. If officials are bound by agreements that prevent them from explaining why one site was chosen over another, that goes to the heart of democratic accountability. And if no NDAs exist, that should be stated plainly. Silence only deepens suspicion.

Winnipeg needs housing. That is not in dispute. But how housing is built matters. Site selection matters. Spillover impacts matter. Transparency matters. And whether the public can clearly see who benefits matters.

The mayor has described this proposal as a win-win situation. It is a tidy phrase, but an incomplete one. A true win-win should be easy to explain in plain terms, without caveats, without deferred answers, and without asking residents to accept uncertainty as the price of progress. Right now, the wins are described mostly in abstractions — targets met, timelines advanced, boxes checked. What remains unclear is how everyday impacts are being balanced, how risks are being absorbed, and how costs — financial, legal, and social — are being distributed.

When a win-win requires one side to give up land, parking, certainty, and peace of mind while being told the details will come later, it is fair to ask whether the benefits are truly shared.

So the question remains. Win-win for whom? And who, precisely, is positioned to benefit most?

If that answer cannot be stated plainly and publicly, without NDAs, without jargon, and without deflection, the label begins to sound less like a conclusion and more like a sales pitch. Housing must be built in this city. But a genuine win-win is not declared — it is demonstrated. Until residents can clearly see who gains, who gives, and why this site was chosen above all others, skepticism is not opposition. It is the public doing its job.